Leadership

Responding to a Worldwide Health Crisis and Travel Restrictions

2017 Comprehensive University of Iowa

Through its global initiatives and community outreach efforts, the University of Iowa (UI), well-known for its Iowa Writers’ Workshop, has excelled in recent years in welcoming the world to its campus in Iowa City. The campus, situated on the former grounds of Iowa’s first state capital, is integrated into the heart of downtown. The UI’s 33,000 students—4,300 of whom are international—make up nearly half the town’s population.

Situated in a central location on campus, the UI International Programs (IP) office serves as the hub for international activity. In addition to study abroad and international student and scholar services, IP also offers grants and funding support to faculty and students and provides a number of intercultural training opportunities.

Senior Leadership Pushes the Internationalization Agenda

Internationalization at the UI has been more than 20 years in the making, according to Downing Thomas, PhD, associate provost and dean of international programs. “If you look back 20 years, international activities at the university were largely a boutique operation for students in humanities and social sciences. It’s taken some time to gain momentum, but I think that now we’re seeing that the success and the true value of internationalization occurs when it is riveted to the core missions of the institution,” says Thomas, who also serves as the UI’s senior international officer.

Thomas’s position as dean was created in the late 1990s, when former university president Mary Sue Coleman, PhD, recognized that the institution needed senior leadership to advance its internationalization agenda.

Former provost Barry Butler, PhD, who left the UI in March 2017, adds that Coleman and then-provost John Whitmore, PhD, also provided funding to each college and asked them to come up with creative ways to internationalize the curriculum.

At the time, Butler, associate dean of engineering, used the seed funding to start the Virtual International Project program, which drew on emerging industry practices for working in remote teams. Engineering students were able to collaborate with peers abroad to work on international design projects. Since the initial partnership with Aix-Marseille University in France, the program has expanded to include Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

Current president Bruce Harreld plans to continue building on the legacy of his predecessors. “Moving forward we hope to be more purposeful in designing an international experience specifically augmenting each student’s on-campus work and career interests,” he says.

Community Outreach As a Cornerstone of Campus Internationalization

A key feature of the UI’s internationalization efforts is its community outreach initiatives. IP currently has seven full-time staff that work exclusively with communications efforts.

“The UI strives to serve not only its students but all citizens of the state. We need to do all we can to share with fellow Iowans the groundbreaking research that happens on our campus and in collaboration with international partners,” says Joan Kjaer, director of communications and relations for International Programs.

International Programs’s signature event is the annual Provost’s Global Forum, which brings together experts from a variety of disciplines to discuss international and global issues.

Full-time faculty are invited to submit a proposal for an award of up to $20,000 to bring speakers to campus. The 2016 Global Forum included an artistic exhibition, a multidisciplinary academic conference, and an undergraduate course on the redefinition of the nation-state in the twenty-first century. The 2017 forum focused on women’s health and the environment.

“It’s an opportunity to focus on a specific issue or topic and have experts from around the country and around the world engaging with our faculty and students,” Thomas says.

Another initiative is WorldCanvass, a monthly radio, television, and Internet program that Kjaer describes as “International Programs’s largest public outreach initiative.” Programs are recorded before a live audience and distributed over television, YouTube, iTunes, radio, and the IP website.

“WorldCanvass conversations are focused on themes that are international in scope. They’re thoughtful, reflective, and inspiring, and we tape the live programs for multiplatform distribution. Interested audience members anywhere in Iowa or the world can enjoy them in the comfort of their home, their office, or their car. We want to reach people where they are and not be limited by time or place,” says Kjaer, who also hosts WorldCanvass.

IP also works with outreach to local K–12 schools. Through the International Classroom Journey program, teachers can enhance students’ understanding of unfamiliar parts of the world by bringing international guests into the classroom to talk about their home countries. For more than 15 years, International Programs and the College of Education have also partnered to present the Teacher’s Institute on Global Education with the goal of helping K–12 educators from around Iowa integrate global perspectives into their classrooms.

Exploring the World Through Writing

Another major outreach effort is the International Writing Program. Since 1967, more than 1,400 writers from more than 150 countries have been in residence at the University of Iowa through its International Writing Program (IWP). The IWP hosts 30–35 well-known authors, poets, and novelists every fall for a three-month residency. Notable alumni include Nobel literature laureates Mo Yan from China and Orhan Pamuk from Turkey.

The IWP, which celebrates its 50th anniversary in 2017, was founded during the Cold War with the goal of bringing together writers from around the world. “It was a place where writers from the Soviet Bloc could meet writers from the west and have free and frank exchanges of ideas,” says Christopher Merrill, IWP director.

Merrill says that since 9/11, there has been a shift at IWP toward a focus on the Islamic world. Because the majority of the IWP’s funding has come from the U.S. State Department and various embassies, much of the program is focused on public diplomacy and cultural exchange.

“After 9/11, we’ve been involved in conversations about the ways in which cultural diplomacy can be a part of the larger diplomatic strategy. And so we started to think of cultural diplomacy as a two-way exchange,” Merrill adds.

As a result, IWP has also started taking groups of U.S. students abroad, hosting symposia in countries such as Greece and Morocco.

To reach an even wider international audience, IWP eventually developed a robust distance-learning program. Since 2012, it has offered more than 30 distinct MOOCs, courses, exchanges, and events on different topics related to fiction, nonfiction, poetry, and plays. In addition, IWP runs a two-week summer writing program at the University of Iowa for young writers, ages 16-19, with workshops taught in English, Arabic, and Russian.

The IWP led the charge in gaining Iowa City’s designation as a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) City of Literature in 2008. As a UNESCO City of Literature, Iowa City also has an obligation to mentor aspiring cities. Merrill subsequently worked with the Iraqi deputy minister of culture to help Baghdad become a City of Literature in 2015. The connection to Baghdad came out of the connections to the Iraqi literary community made possible through the IWP.

“We like to think we’re helping to jump-start a conversation about world literature,” says Merrill.

UI Creates a Welcoming Atmosphere for International Students

According to the UI, its international student population has nearly doubled over the last 10 years, from around 2,200 in 2006 to 4,300 in 2016. Most of the growth has occurred at the undergraduate level. The top three countries represented on the UI campus are China, India, and South Korea.

To accommodate the growth, International Student and Scholar Services (ISSS) has implemented several programs to support its international population and to promote their integration into life on the UI campus in addition to its standard immigration advising.

One of the initial initiatives in 2008 was the creation of the International Student Committee, which was tasked with auditing existing services and programming for international students to ensure that adequate infrastructure was in place. The committee’s goals have subsequently expanded.

“It drives resources from all units across campus, from housing, public safety, counseling, the registrar’s office, and the colleges to try and make sure that [international students] have the best student experience they can,” says Doug Lee, assistant provost of international programs.

ISSS also runs a number of intercultural programs targeting the wider campus community. The Bridging Domestic and Global Diversity certificate is a leadership program designed to educate students to adapt to cultural differences. Approximately 25 domestic and international students participate in diversity and intercultural training every spring semester. Participants also plan the Bridge Open Forum, an intercultural event to educate the campus about intercultural issues.

The Building Our Global Community certificate is a professional development program that helps UI faculty and staff support international students and scholars. To earn the certificate, participants attend a series of sessions on topics such as helping international students with the cultural adjustment process and the basics of F-1 and J-1 immigration regulations.

The UI also offers individual and group mental health counseling services in English, Spanish, and Mandarin. Students first learn about the University Counseling Service (UCS) at their orientation, when one of the doctors presents about mental health and available counseling services.

“In efforts to meet the needs of students having mental health concerns, the UCS acknowledges that communicating about emotions, insight, and internal conflicts can be highly culturally based and varies greatly due to the construction of how we think about ourselves based on variances within language. As such, the UCS desires to remove as many barriers as possible by providing opportunities for students to communicate in the language that best represents their experience within UCS resource limits,” says UCS director Barry A. Schreier, PhD.

According to Lee Seedorff, ISSS senior associate director, support for using mental health services comes from the students. For example, a group of Chinese students interested in mental health has started a student organization called Heart Workshop, which helps other Chinese students become aware of the support available. Another group is Active Minds, which focuses on mental health awareness and support for both international and domestic students.

In the last few years, the UI has also used technology to reach out to prospective students and parents. According to Lee, it holds welcome sessions in Beijing and Shanghai for incoming Chinese students. To reach students from other countries, they are also creating orientation webinars that students can watch from anywhere in the world. They have also started broadcasting graduations online in Arabic, Korean, Mandarin, Farsi, and Spanish for families who are unable to travel to Iowa City for the ceremony.

The Tippie College of Business, one of the most internationalized schools on campus, has been at the forefront of efforts to integrate international students into life at UI. Around 15 percent of its undergraduates are international, compared with 10 percent on the campus as a whole. To support its large international population, Tippie has created opportunities outside of the classroom such as an international buddy program, which pairs domestic and international students and is open to students from across the campus.

Comprehensive Support for Education and Research Opportunities Abroad

According to the 2016 Open Doors report, the UI ranks in the top 50 U.S. institutions for study abroad, with 21 percent of all undergraduates going abroad. The UI also has several initiatives that create education abroad opportunities for underrepresented students. The total minority undergraduate population is 14 percent, and 16 percent of all undergraduate study abroad participants were students of color in the 2015–2016 academic year.

There are a number of awards available, including a $500 scholarship for traditionally underrepresented populations, such as first-generation students, students of color, LGBT students, and students with disabilities, to help finance study and research opportunities abroad.

IP also recently collaborated with the UI Center for Diversity Enrichment to host the Council on International Educational Exchange (CIEE) Passport Caravan. IP and CIEE sponsored passports for 116 first-generation students and students of color who were first-time passport holders.

International Programs also receives support from the Stanley-University of Iowa Foundation Support Organization (SUIFSO) to fund research projects abroad. Both undergraduate and graduate students, including students who are not U.S. citizens, can apply for international research grants.

In the past five years, 100 graduate students received a total of $250,000, and 26 undergraduates received a total of $59,000 to conduct international research.

“Every year we have a pool of money for students to do preliminary research, or a creative project. They must be abroad for a month and these are a wonderful starting point to apply for a Fulbright,” says Karen Wachsmuth, PhD, associate director for international fellowships and Fulbright adviser.

The UI has been recognized as a top producer of Fulbright awardees for the last two years. In the 2016–2017 academic year, 15 UI students were awarded grants to conduct research or serve as English teaching assistants abroad.

Wachsmuth sees her outreach and recruitment for Fulbright as a springboard to start more general conversations about opportunities abroad, especially early in a student’s academic career. “There are a lot of different programs going on to start conversations, and fellowships are a part of that because they also encourage students to put together their language training or just things that they’ve learned in their coursework and to apply it to an arena that eventually helps them develop their professional goals,” she says.

“The biggest compliment that I get from students is ‘Even if I don’t get this grant, I’ve learned so much about myself and about where I want to go from doing this,’” Wachsmuth says.

Douglas Baker, who graduated in 2015 with degrees in music and Japanese, spent a year in Japan as a Fulbright fellow. He was able to combine his two majors to investigate the work of a nineteenth-century Japanese composer.

He says that the UI’s position as a research institution gave him the resources he needed to prepare his proposal. “The university has many qualified people, from professors to librarians, who know the ins and outs of creating projects or grant writing or conducting research. Karen [Wachsmuth] and International Programs also provide so much assistance in the application process in terms of information sessions, writing workshops, [and] draft writing get-togethers,” he says.

UI Runs Largest U.S. Study Abroad Program to India

The UI’s single largest study abroad program is the India Winterim, an intensive, three-week field-based program held every January. Due to the program’s overwhelming popularity, no other U.S. college or university in the United States sends more students to India. In 2016–2017, 85 students participated in five different courses.

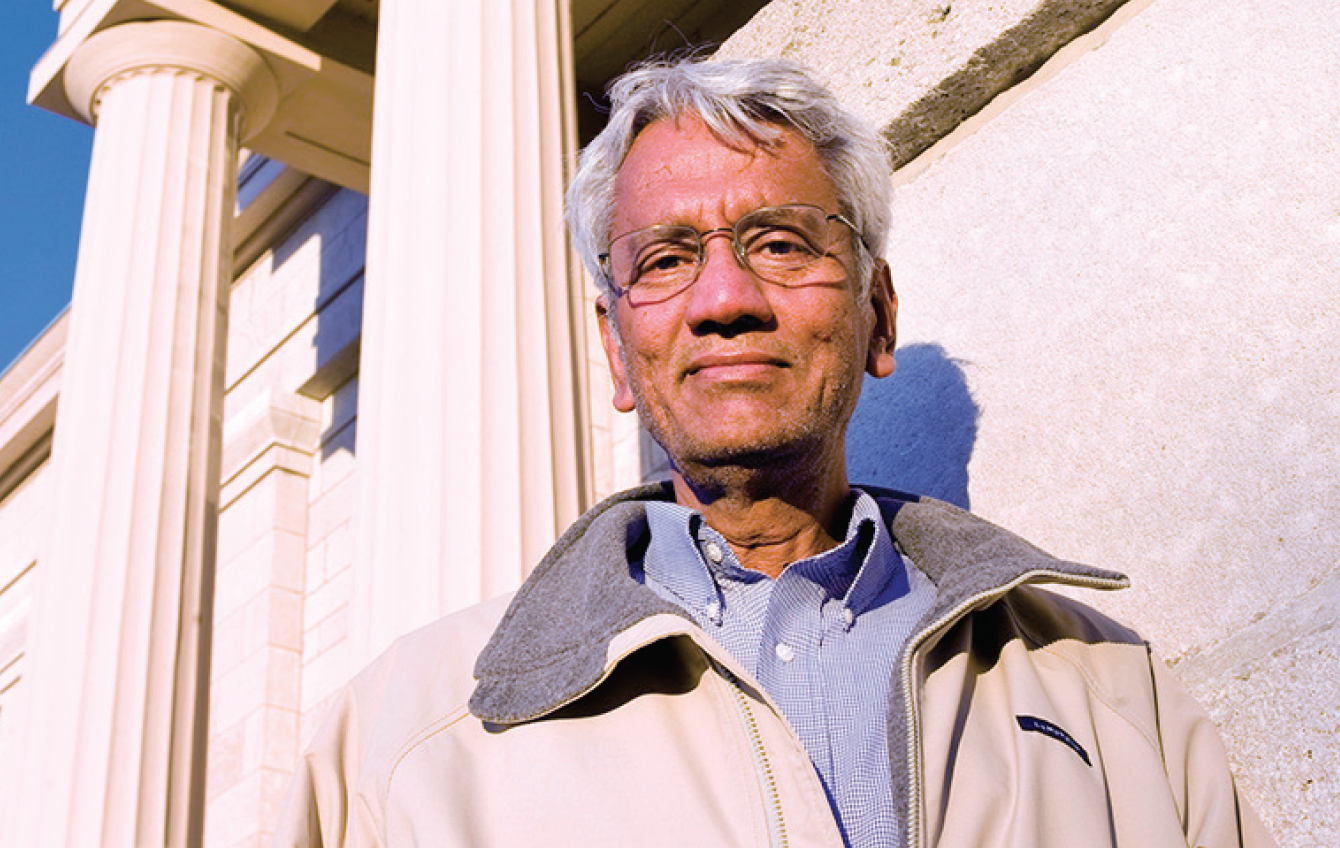

The program is the brainchild of founder Rangaswamy “Raj” Rajagopal, PhD, also a professor of geographical and sustainability sciences. Rajagopal started the program in 2006 and has subsequently sent more than 1,100 students and 60 faculty members to India.

Students are placed at nonprofits and academic institutions through a variety of faculty-led courses in various disciplines, ranging from engineering to art history. Courses have addressed issues such as water poverty, craft traditions, sustainable development, education, and nonprofit management. Students work with Indian partner organizations to learn about their approaches to addressing social issues.

Janice Cousins is a premed and psychology major who traveled to Kerala in South India this past winter break. She took a course titled Pain, Palliative Medicine, and Hospice Care: Learning from Each Other led by a faculty member from the school of medicine. She learned about end-of-life care in India by working with a physician who founded a community-based palliative care program.

“He started this program for people who cannot afford medicine and aren’t getting the correct care. He was really passionate in teaching us about palliative medicine, which considers everything about the disease, including the mental and spiritual aspects. This completely expanded my perspective on medicine. The things I learned in India, I’m not going to learn in medical school here,” Cousins says.

Rajogopal spent six months working with the Indian physician to develop the palliative care course. He says that cultural comparison is one of the key aspects of the program. In the United States, hospice care in an institutional setting is most common, whereas in India, end-of-life care is provided in the patient’s home.

“The lesson learned is that there is no single right model of living life. What we are trying to teach is that America doesn’t necessarily know best. There are different models of evolution, culture, and history,” he says.

Rajagopal says that many students, like Cousins, have come back from India with a desire to go to medical school after participating in courses related to health care.

“All of these kids come back, and they’re renewed. They’re totally fearless. You see people living in extraordinary conditions and doing all these kind of things, and it changes you forever,” he adds.

2017 Comprehensive Santa Monica College

With more than 30,000 students enrolled at its campus in Southern California, including 3,500 international students from more than 110 countries, Santa Monica College (SMC) is one of the most diverse associate’s institutions in the United States. Domestic and international students alike benefit from the college’s Global Citizenship Initiative, which provides a variety of international education opportunities across the SMC campus.

Launched by former college president Chui Tsang, PhD, in 2007, the initiative is a four-pronged strategy that promotes campus internationalization through study abroad, staff and faculty professional development, curriculum development, and international student services. Over the last decade, the initiative has led to the development of several faculty-led programs, an undergraduate research symposium, faculty and staff trips abroad, and a global citizenship requirement for all SMC associate’s degrees.

Global Citizenship Becomes an Institutional Mandate

Dean of International Education Kelley Brayton, who joined SMC in 2008, co-chairs the Global Citizenship Committee with a faculty leader. According to Brayton, “internationalization became a mandate for the institution” under Tsang’s leadership.

The college then convened a task force comprised of faculty and administrators to govern the initiative and to figure out how to make it sustainable beyond the initial funding period. In 2008 the SMC board of trustees adopted the initiative as a strategic priority and committed $200,000 a year for a three-year period. The task force eventually became a permanent standing committee, known as the Global Council, in the faculty senate.

Brayton says the program has been successful due to the support of senior administration, as well as the large amount of financial and human resources dedicated to the initiative. “I have never been at an institution where [internationalization] has had this level of support,” she says.

SMC has continued to provide funding for global citizenship activities, including earmarking $75,000 a year for study abroad scholarships. The college has also successfully pursued two Title VIA grants, which provide federal funding for foreign language, area, and international studies infrastructure-building at U.S. higher education institutions.

Kathryn E. Jeffery, PhD, who became president in 2016, remains committed to the initiative, even in the wake of a state budget crisis. “We are being very guarded around making sure that we continue to support the Global Citizenship Initiative to create opportunities for students. We don’t want that to fall off of the list of priorities,” she says.

Defining Global Citizenship

One of the first steps toward implementing the initiative was defining what “global citizenship” meant for SMC. “Dr. Tsang empowered the campus. He set the direction, but he left it up to us to figure out what exactly global citizenship would look like,” says Gordon Dossett, English professor and one of the original co-chairs of the global citizenship task force.

“Dr. Tsang saw the bigger picture and helped us realize that this was something we could work on as a faculty,” adds Janet Harclerode, chair of the English as a Second Language (ESL) department.

In 2008 SMC adopted its formal definition of global citizenship: “To be a global citizen, one is knowledgeable of peoples, customs and cultures in regions of the world beyond one’s own; understands the interdependence that holds both promise and peril for the future of the global community; and is committed to combining one’s learning with a dedication to foster a livable, sustainable world.”

According to Vice President of Academic Affairs Georgia Lorenz, PhD, the process of defining “global citizenship” eventually led to the adoption of global citizenship as an institutional learning outcome, which has had important implications for accreditation. “For something to become an institutional learning outcome is really significant. At the course and program levels, faculty will map their course outcomes to the competencies related to the institutional learning outcome” she explains.

Faculty-Led Programs Revitalize Study Abroad

When Santa Monica College student Ariana Kirsey traveled to South Africa last year, she couldn’t have imagined that sleeping in a tree house in Kruger National Park would be life changing.

Kirsey is one of 25 students who studied abroad through SMC’s faculty-led program to South Africa in January 2017. In addition to South Africa, SMC also runs annual trips to Belize and Guatemala through its Latin America Education program.

Each year, SMC sends more than 80 students abroad through its various study abroad programs, which range from one-week courses over spring break to six-week courses that are offered during winter or summer sessions.

Although SMC has offered study abroad programs since the 1980s, with the Global Citizenship Initiative the college made a conscious effort to switch from third-party providers to developing faculty-led programs that also allow SMC professors an opportunity to travel.

Every year the college puts out a call for proposals to recruit faculty who are interested in leading trips abroad. Two professors travel with the students on each trip, and both part-time and full-time faculty are eligible to participate.

“We try to have a full-time lead faculty and then have a second faculty who may not have led study abroad before. They colead the first year, and then the second year the idea is that they would take on the lead. We wanted to rotate it so it wasn’t just a select few who could do it,” Brayton says.

SMC also offers a one-credit course, Field Studies Abroad, which launched in 2016. The program was developed specifically to target students who might not be able to travel for longer periods of time. Students travel with a faculty member for seven to 10 days over spring break.

The college approved a one-credit class called Global Studies 35 that can be customized depending on the destination. Brayton says that Field Studies courses have created opportunities for students and faculty alike because of their shorter duration.

Art history major Megan Dobbs says the Field Studies model was quite convenient in terms of time and affordability. She traveled to Denmark in March 2017 as part of a course titled Vikings, Socialism, and Sustainability: Copenhagen Past and Present.

“The trip took me out of my personal bubble and reminded me to think of the world on a much grander scale. This trip continues to remind me that I need to make an effort to step out of my comfort zone and have new experiences,” says Dobbs, who transferred to the University of California-Berkeley in fall 2017.

The college also strives to keep its study abroad programs affordable. “We really work hard on creating very low-cost study abroad. We have become an informal travel agent here at SMC and we work with in-country vendors,” Brayton explains.

The college provides $75,000 in study abroad scholarships every year, and more than half of all students going abroad receive $500 to $2,000 based on need. Many students are first-generation college students, and more than half of SMC’s study abroad participants are minorities. In addition, they are seeing an increased number of international students joining faculty-led programs.

“A lot of our students have never left LA before. Study abroad is an experience that can really shift their perspectives on what it means to be a global citizen,” says Associate Dean of Student Life Nancy Grass, PhD, who led students to South Africa in 2008 and 2012.

Comprehensive Support for International Students

For the last five years, Santa Monica College has had the second largest international student population of any community college in the United States, according to the Institute of International Education’s Open Doors data. SMC attracts students from around the world largely because of its reputation as a top transfer school.

While some students pursue shorter academic certificates, the majority of its 3,500 international students seek admission to nearby four-year institutions such as the various campuses of the University of California (UC). International students receive academic and immigration advising, among other support services, through the International Education Center and the International Education Counseling Center.

Omar Bishr, an economics major from Egypt, plans to transfer to the University of California. “From the moment I applied, the international office responded to all of my concerns. When I came to SMC, I felt like I was really welcomed to the school and that my presence matters. I really liked that I was given a presentation by counselors explaining to me the system of the college and how to choose my classes in order to transfer,” he says.

One initiative that seeks to promote interaction between international and domestic students is a language and culture exchange program run jointly between the modern languages and ESL departments. International students are paired with domestic students studying their language.

“We create an online forum for them and have an orientation. They can meet on that day, but if they don’t then they can go into the forum and introduce themselves and find people for language exchange online,” says Liz Koening, an ESL faculty member.

Approximately 130 students participate per semester. Music major Nahalia Samuels says she took part in order to practice her language skills with a native speaker.

“For me, having a language partner for Korean 1 and Korean 2 made all the difference in my reading, writing and speaking skills. I also wished to learn more about the...culture of the language I’m studying and to offer help as a native English speaker towards my ESL partner. I feel the program helps foreign students to connect with the campus community and expose us domestic students to a seemingly hidden population on campus,” she says.

Professional Development Helps Internationalize the Curriculum

Early on, SMC recognized that it was necessary to internationalize the faculty in order to reach the long-term goal of campus internationalization, especially in the classroom. The Global Citizenship Initiative thus led to the creation of a number of professional development opportunities abroad for faculty and staff.

In 2007, the first group of SMC faculty and staff traveled to Austria to attend the Salzburg Global Seminar, where they learned about topics such as intercultural communication and social justice. Other cohorts have subsequently visited the Beijing Center for Chinese Studies in China and Bahcesehir University in Istanbul, Turkey, with the last group traveling in 2015. Over the past 10 years, more than 125 SMC faculty and staff participated in the professional development programs to Austria, China, and Turkey.

Peggy Kravitz, international education counselor, traveled to Austria, China, and Turkey. “It was a fabulous way to learn about those cultures, which of course I deal with in my work with international students,” she says.

Grass, who traveled to China, adds that one of the greatest benefits of the programs is the fact it was open to all full-time employees on campus.

“It wasn’t just faculty or administrators who could go, but technicians and custodians could apply as well. They really took a cross-section of the college that allowed for people to really get to know each other in a whole new way,” she says.

Brayton says the idea was to help staff who are often on the front line of student services gain a greater appreciation for the international student experience at SMC. “Classified staff are the ones who have a lot of casual interactions with students every day. The more they understand some of the challenges of being abroad, the more they that can connect with our international student population,” she says.

Upon their return to campus, faculty members must develop modules for their courses, and staff are to participate in international activities on campus, such as International Education Week.

In addition to the trips abroad, faculty can apply for a number of Global Grants ranging from $3,000 to $10,000 that fund projects and events, such as speakers, film screenings, and field trips, throughout the year. Harclerode, for example, received a Global Grant to take her ESL classes to various sites around Los Angeles, including the Watts Towers and the Los Angeles River. “The idea was to take them to the parts of LA they might not get to on their own,” she says.

Promoting Global Citizenship Through Student Research

To weave the idea of global citizenship into the fabric of campus life, SMC chooses a theme for each academic year and encourages faculty to develop related course modules. The current theme—“Gender Equity: Is Equity Enough?”—has been running for two years. In 2017–2018, the campus is exploring the topic of “Promise and Peril of a Global Community.” Previous years’ themes have included water, food, poverty and wealth, and peace and security.

The campus also holds an annual research symposium, where students are invited to submit and present academic and creative projects related to the annual academic theme.

Grass, who chaired the first symposium in 2010, says the idea for a campuswide research symposium emerged from the need to better prepare students to transfer to four-year universities: “When students come from the community college, even if they are really well prepared academically, they’re not ready to jump into junior-level research projects. Having the symposium encouraged faculty to have students do original research around this idea of global citizenship.”

“When we put out the call for proposals, it allows students to put forward what global citizenship means to them in the context of their education,” adds Delphine Broccard, communications professor and current symposium chair. “We can really discuss what global citizenship means in the different disciplines.”

Students submit proposals for projects ranging from short films, persuasive speeches, and photography to responses to study abroad experiences and Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM) research. Students can win cash prizes for the best entries in different categories. In 2016, Kenta Tanaka, an international student from Japan, won the President’s Award and $500 for a design project that explored the theme of gender equity in fashion. “I mixed menswear and womenswear. In fashion, we call it gender blur,” he says.

Global Citizenship Spans the Curriculum

SMC has used funding from one of its two Title VIA grants to develop a global studies major. Global studies at Santa Monica is an interdisciplinary program designed to increase students’ knowledge and understanding of the processes of globalization and their impacts on societies, cultures, and environments around the world. Coursework includes world geography, international political economy, experiential learning, and foreign language.

The Global Citizenship Initiative has also given impetus to the development of a global citizenship degree requirement for all students receiving an associate’s degree. Students can meet the requirement either by studying abroad or taking an approved global citizenship course.

“The reality is that not a lot of students can participate in study abroad. But where students are going to be the most impacted by global learning is in the classroom. Infusing global perspectives into the general education curriculum is where we can reach a lot of students. Hopefully, that exposure highlights some of the international opportunities for them, not just here at Santa Monica but beyond,” Brayton says.

Management Development Program (MDP) Trainer

2005 Comprehensive Howard Community College

Near the end of the faculty’s first meeting with Mary Ellen Duncan after she became president of Howard Community College in 1998, Spanish professor Cheryl Berman stood up and asked with unwonted diffidence, “Can I start study abroad programs here?” “You don’t have study abroad programs? Of course, you better start study abroad programs,” replied Duncan, a onetime high school Latin teacher who had previously expanded the horizons of SUNY’s College of Technology at Delhi during seven years at the helm of that school in New York’s Catskill Mountains.

Today Howard Community College regularly sends dozens of students on a Spanish immersion program in Cuernavaca, Mexico, each January, and it offers opportunities to study in China, Italy, Greece, Russia, and Costa Rica. It has student and faculty exchanges as well with institutions in Denmark and Turkey, awards scholarships for study abroad, and has partnerships with Dickinson College and the College of Notre Dame of Maryland that allow top Howard students entry to additional summer programs on several continents.

A Very Internationally-Oriented Community College

Howard’s World Languages department—Cheryl Berman is the director—regularly teaches Arabic, French, German, Italian, and Spanish, and through its Critical Languages program provides tutors and online resources for students to learn Chinese, Russian, Korean, and Greek. It has a thriving English Language Institute, as well as 174 international students among the 6,700 students seeking associate degrees. Howard faculty, administrators, and even its board of trustees are active in Community Colleges for International Development, Inc., a consortium of 90 community colleges involved in exchanges and development projects in more than 40 countries. Duncan chaired the consortium in 2005.

Howard is in the midst of a building boom, with work completed on a high-tech Instructional Laboratory Building, a performing arts complex well under way, and a $28 million student services building in the offing. Howard was born in 1970 with advantages, sitting in the middle of one of the wealthiest counties in the United States, midway between Washington, D.C. and Baltimore. Columbia, its hometown, is itself an experiment in living, a planned community created in the turbulent 1960s by developer James Rouse, known for revitalizing Baltimore’s Inner Harbor and breathing new life into Boston’s Faneuil Hall, as a place where all races and classes could live and work together, with parks and pathways and a small-town atmosphere. It has not worked out entirely as Rouse dreamed; most of Columbia’s 100,000 residents commute to jobs in Washington and Baltimore.

Howard Community College is only the seventh largest of Maryland’s 16 community colleges, but enjoys an outsized reputation as a place that cultivates and rewards innovative thinking, from entrepreneurial workforce training programs to a much honored theater program that boasts the only professional Equity theater group in the country at a community college. The president and vice-president of the student government last year were from Germany and Syria respectively, and Howard has garnered several national awards for internationalizing its curriculum. Duncan said it is fitting for a place founded as a “little Shangri-La. We’re in a community that has people from all over the world.”

Faculty and Administration Work Together on Internationalization

The emphasis on the international spread throughout academic departments after business professor Rebecca Mihelcic became coordinator of international education in 1999. Vice President of Academic Affairs Ron Roberson, a former chair of the humanities division and fine arts professor, said, “When Beckie expressed an interest in really going after the development of an international education program, I was very excited.” Roberson, who spent a year as a Fulbright scholar painting and studying art history at the University of Louvain in Belgium after his graduation from Morgan State University, added, “Nothing happens in education unless you’ve got somebody on fire about an issue. Beckie had the conviction that this was a critical direction for the institution.” Mihelcic built on groundwork that Margaret M. Mohler laid as director of the International Business and Education Center from 1995 to 1999 at Howard. But Mihelcic cast the net wider, encouraging faculty in every program to take advantage of international travel and research opportunities and to incorporate international content into their classes.

Patti English, who 10 years ago started Howard’s cardiovascular technology program, which trains technicians to work in cardiac cath labs in leading Baltimore and Washington hospitals, remembers getting a survey from Mihelcic five years ago encouraging faculty to think of ways to internationalize their courses. She sent it back with a note saying, “Beckie, I would love to, but I can’t foresee anything in my field being international.” When pressed, English recalled that some countries had approached her professional association for advice on setting up cardiac cath labs. “Patti, what do you think of that?” asked Mihelcic.

In January 2004, English and Jeanette Jeffrey, an assistant professor of health science who teaches nutrition and community health, took four students to Costa Rica for a comparative study of the country’s healthcare practices. They visited public and private hospitals and clinics, and will be returning with more students in 2006.

“Everyone is incredibly supportive of internationalizing Howard, from the president on down,” said Jeffrey, who also teaches at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. Last year Roberson gave her a professional development grant to do field research in Switzerland under the auspices of UMBC’s health administration policy program.

“You have to get the faculty on board before you get the students,” said Mihelcic, who raised $6,000 last year for study abroad scholarships by renting to colleagues a rustic cabin she owns. “Once faculty start thinking in international terms and they start talking international, it becomes a natural thing. It’s not something we’re adding to the curriculum. It’s something that’s part of our education.”

Offering Students Mirrors and Windows

Helen Buss Mitchell, a philosophy professor and director of women’s studies, always had been passionate about exposing philosophy students to the widest possible range of thought and beliefs about existence, not just the Western tradition. When she complained about the deletion of women’s voices from a popular philosophy textbook in the early 1990s, the publisher’s representatives asked Mitchell to write her own textbook. The result was Roots of Wisdom, now in its fourth edition and being translated into Chinese and Spanish. Mitchell also produced a television course, “For the Love of Wisdom,” distributed by PBS. “My life has taken quite a different turn and it’s been wonderful,” said Mitchell.

Mitchell said Howard Community College’s internationalism is partly a product of “where we are, between Baltimore and Washington. We’ve got embassies 25 minutes away, and events of all kinds. We’re positioned in a place where the world comes to us, and we make a special effort to be, in Diogenes’s famous phrase, ‘citizens of the world.’”

“Twelve years ago, when I first started teaching ‘Religions of the World,’ most people in the class were Christians or a few Jews, that was it. Now every semester I’ve got Muslim students in the class and often Hindu students,” she said. “It makes for very interesting discussions.”

At Howard, Mitchell said, “We offer our students mirrors as well as windows. We want our students to see through the windows into whatever it is we want them to see. But we’re offering mirrors as well so that in my book and in a lot of things going on here, students see themselves reflected.”

World Languages Program

The college renamed its “foreign” language program “world” languages several years ago. “I love that,” said President Duncan, who took the Spanish immersion classes in Cuernavaca herself. “‘World’ languages sounds much more inviting.” The college celebrated World Languages Day last March with a day- and eveninglong series of 15 events ranging from skits and songs to lectures and a Chinese calligraphy demonstration (Cheryl Berman served as the impresario, wearing a peasant dress she brought back from Chiapas, Mexico). To accommodate day and evening students, the dancing, yodeling, mariachi music, and more went on from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. and again from 5 p.m. to 9 p.m. The language classes , draw students of all ages, from teenagers to octogenarians. “Cheryl is such a strong and joyful force, drawing people into the culture and languages,” said Jean Thiebaux, a retired mathematician for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration who has taken Spanish classes here and in Cuernavaca.

The immersion classes in Mexico are taught at Universidad Internacional in Cuernavaca, which arranges stays with host families for students from many U.S. colleges and universities. Jonathan Henry, who works in international promotions for the Mexican university, said, “To me, Howard seems like a regular university.”

Universidad Internacional sent faculty member Carlos Guzman on a one-semester teaching exchange to Howard in 2003. His courses were so popular that Howard asked him to stay for a second semester, and then for a second full year. “This will be my last [semester]. It’s time for other faculty to have the opportunity,” said Guzman.

Berman was a French major in college whose interest in Spanish was awakened when she and her husband adopted twin girls from Bogotá, Colombia. “I fell in love with everything Spanish, with the cultures, the whole thing,” she said.

Berman has a gift for picking up languages—and for convincing others to give it a go. “You just have to role model passion and energy and expectations and all those things, and they pick and choose what they take out of it,” said Berman.

When Berman set out to explore the first study abroad opportunity for Howard, a Spanish professor from a State University of New York campus shared a wealth of advice about finding immersion classes in Latin America. She also informed her about the myriad of details related to preparing students for the experience—everything from shots to release forms.

Partnerships with U.S and Danish Governments Bear Fruit

Howard’s critical language program grew in part out of Berman’s interest and involvement in the Interagency Language Roundtable (www.govtilr.org), a half-century-old network of federal agencies that share information and resources about teaching and learning languages. Howard hosted a Roundtable meeting in April that explored the roles of community colleges in delivering foreign language education in the United States, and the Roundtable also held its annual summer research showcase at Howard in July 2005.

The government has identified six languages as critical to U.S. national security—Korean, Chinese, Farsi, Russian, Spanish, and Arabic—and Howard now offers regular or special instruction in five of them. Berman believes that since these languages have been identified as a national priority, educators and schools at every level should do their part to teach them. The students in a Korean or Chinese critical language tutoring session at Howard may never end up at the Defense Language Institute’s Foreign Language Center in Monterey, California, but they could become part of a groundswell that produces more candidates for advanced training. “It’s like a [youth] soccer league, you know? One that has both travel teams and the neighborhood kids?” said Berman. “It’s like, ‘Everybody—high schools, community colleges, four-year colleges and universities—just put in your players, and somehow enough will emerge at the top.’” At Howard, she added, “we’re the neighborhood squad, and that’s how I like it.”

Howard got a Danish connection thanks to a State Departmentarranged visit by the Danish education minister. Roberson was invited to a conference in Denmark with other community college representatives. He and representatives from three Danish colleges eventually decided to develop an information technology exchange program. “I thought that would be the easiest thing around which to develop an articulation. The skill sets and the software are the same, regardless of where you are; you’re still dealing with Microsoft and Apple,” he said.

“I proposed a tactical project that we could do ourselves, regardless of whether we got external funding,” said Roberson, whose office is filled with portraits he has painted in styles from that of Rembrandt to stark realism.

Faculty from the three Danish institutes—Neilsbrock Copenhagen Business College, Odense Technical College, and Tietgen Business College—visited Howard and jointly worked out the articulation agreement so that Danish students could spend their third semester in Howard and U.S. Information Technology (IT) majors could spend a semester in Denmark, where IT courses are routinely taught in English.

What do the Danes have to teach U.S. students headed toward careers as programmers?

“It was really happenstance, in all honesty, that this partnership was with Denmark,” Roberson said. “The fact is, though, that the year that their minister of education visited our campus, their business and technical school system won the prize as the best in the European Union. I was very curious how it was [that] they were organizing their programs. We have learned quite a bit from our collaboration. They design programs very differently. They have a holistic design. We offer a menu list and students pick from that menu. Their holistic approach was very interesting to us, the fact that they taught business and marketing and entrepreneurship as part of their IT programs. What IT program in the United States does that?”

Long-term internships were also built into the Danish regimen, so that after a year of classes, all students spent an entire semester working in industry before returning for another semester of coursework. “They really are very connected with the industry. They learn not only the abstractions of the education program, but they actually understand how it works in the real world,” said Roberson.

“The fruits are really just beginning for us. We sent our first student over last fall; they have sent seven so far,” he said. The Howard student, with support from the community college, studied multimedia design in Odense—birthplace of Hans Christian Andersen, two hours by train from Copenhagen—and “had a wonderful experience.” The Danish exchange students, meanwhile, who had been taking English since elementary school, all placed into college-level English at Howard and excelled in their studies here. The community college, which has no dorms, rented an apartment for these exchange students. “For the Danes, this is nothing special. They have many of these agreements with many different countries. The students have a lot of choices. We represent another choice for their students,” said Roberson.

Consortium Teams with Turkish Technical Colleges

In consortium with Delaware Technical & Community College and Northampton College in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, Howard is now attempting to forge an extensive partnership with technical colleges across Turkey. Howard will be lending its expertise in preparing English as a Second Language (ESL) teachers as well as in teaching computer sciences, while Delaware Tech and Northampton will impart their expertise in other areas. Vice President of Student Services Kathleen Hetherington and ESL Director Jean Svacina made an exploratory trip to Greece and Turkey in 2002 under the auspices of Community Colleges for International Development. Rebecca Price, the ESL program administrator, was headed to Turkey this spring along with a team of Howard administrators to work out the details and to gauge whether the Turkish computer science students were ready for English-language instruction at Howard after a year of studies at their home institutions. Howard also was sending four students and a faculty member to study in Ankara in June 2005.

The English skills of the Turkish students are not as advanced as those of the students in Denmark. Price, whose ESL program has won both state and national awards, said, “They may need to do a semester here in our language institute, or we may have to go train their teachers so that the instruction they get in English is better before they come here.”

“The Turkish government is totally committed to this. This is not just a couple of schools. If it works, this will be a program available to all two-year schools in Turkey,” she added.

Working with Local Business and Industry

The Howard Division of Continuing Education & Workforce Development has a long history of responsiveness to the needs of Maryland businesses. Patricia M. Keeton, executive director of workforce development, said, “Many Howard County companies are trying to internationalize their business. We have a contract right now with a local company to train 25 Kuwaitis in fundamentals of electronics this summer in order to help that company then teach them how to use their equipment. We’re able to assist businesses in translation efforts, we’re able to help them train employees who speak English as a second language.”

Minah Woo, a program counselor in the English Language Institute (ELI), said one reason its enrollments have grown is that “we have four levels of classes and a variety of classes at each level. We’ve established ELI custom class options. The student who won the scholarship to art school was taking nine credits of ELI and three credits of art class.” Some institute students bound for U.S. graduate or professional schools come to Howard’s ELI after scoring over 600 on the Test of English as a Foreign Language.

“Students come and say, ‘I have a real need in public speaking.’ Others say, “I can speak fine, but they don’t understand my pronunciation,’ or they come and say, ‘I need to do more professional writing.’ They can come here and take the classes they need, whereas other institutes basically have morning writing and grammar and afternoon reading and conversation.”

JoAnn D. Hawkins, associate vice president of the Division of Continuing Education & Workforce Development, said tool manufacturer Black & Decker is sending executives to Chinese classes at Howard so they can communicate with employees at a plant in Soochow, China. “They found that when they went over, even though they had translators with them” some of what they said was lost in translation. Her division also is set to help a company that trains firefighters for Malaysia produce the country’s first emergency medical technicians. That would involve sending two Howard instructors to Malaysia for five weeks over the summer, then hosting a dozen or more trainees here for five more weeks.

Hawkins, who used to lead study trips to Europe and Asia that the college organized for community members, said the spirit of cooperation between the credit and noncredit sides at Howard is unusual. “We don’t have silos. Whoever can do a program best does it,” she said.

Vladimir Marinich, a Howard history professor, and his wife Barbara Livieratos, the associate director of research, regularly take students and other community members on a study trip to Russia that is built around a cruise on the Volga between Moscow and St. Petersburg. They have devoted profits from the trip to a study abroad scholarship fund and have raised $40,000 on four trips since 2000. Kristy Herod, 25, won a $3,200 scholarship that paid for her trip to Russia. The Hawaiian-born Herod, now pursuing her bachelor’s degree at the University of Maryland, said, “There’s nothing better than actually being able to say, ‘Well, I read this in a book, but this is where it happened and here I am.”

Scholarship Students Are Looking for International Experience

The Rouse Scholars Program—named after the founder of Columbia—has long been a source of pride for Howard. Barbara Greenfeld, director of admissions and advising, said the selective admissions program “is unique among community colleges across the nation.” It was begun 13 years ago and its reach has been extended by a partnership with Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, that allows Rouse scholars to go on Dickinson summer study abroad programs. Dickinson, which was featured in the NAFSA’s Internationalizing the Campus 2003 report, runs 35 study abroad programs in 22 countries on six continents. Patrick Ginssinger, a 2003 Howard graduate, went on an archaeological dig in Scotland with students from Dickinson and the University of Durham. Hafsa Bora ’05, who went to Dickinson’s center in Bologna, Italy, in summer 2004, said, “I loved everything about my … summer study abroad experience. I learned so much and can hardly wait to return.” Other Rouse scholars have studied in London and Hong Kong, in some cases with tuition waivers or reductions. Howard also has formed a study abroad partnership with the College of Notre Dame of Maryland.

Greenfeld said Howard regularly asks its Rouse scholars what they were looking for in a college. In recent years, the answers were clear. “They want housing and they want an international travel experience, and they want to know how we’re going to provide that for them,” she said.

Providing the Encouragement and Support for International Programs

Howard is considering building its first dorms not just to keep attracting top caliber local students, but to make it even more inviting for international students. The lack of dormitories has been an obstacle the college has had to overcome in forging partnerships, both with the Danish colleges and a new arrangement with Soochow University in Suzhou, China. But Howard hasn’t let that curb its momentum.

There’s a lesson in that for other colleges, said Kate Hetherington, who is herself a graduate of and former administrator at the Community College of Philadelphia (also featured in Internationalizing the Campus 2003). Obstacles can be overcome. “Opportunities do show up at your doorstep, and when they do, it’s a matter of saying, ‘Let’s give this a try,’ rather than, ‘No, we don’t have housing,’ rather than looking at all the nos,” said Hetherington. “There’s been a lot of freedom [at Howard] for people to explore ideas around the theme of global education….Essentially we’ve asked people to let their creative juices flow and given them the freedom and support to go ahead.”

Building Connections with China

Roberson traveled to China in 2004 in quest of new partners. When Duncan was president of SUNY Delhi, her hospitality program exchanged students and faculty each year with a partner in China. As the president said of her receptiveness to creating study abroad opportunities at Howard, “It’s hard working in China, but I couldn’t believe that this community wouldn’t want that experience for their children.”

Qing Qing Li, a professor of English at Tianjin University of Commerce in China, spent a year at SUNY Delhi teaching Chinese culture classes a decade ago, and President Duncan invited her to reprise that role at Howard this past year. Li, whose education was disrupted by the Cultural Revolution in the 1970s, said she has gained insights at Howard that will help her students back in Tianjin. She is auditing Helen Mitchell’s “Religions of the World” course and deepening her knowledge of Western culture.

“I grew up in the ’60s and 70s in a kind of culture vacuum. I did not really know much about my own culture,” said Li, who demonstrated the art of Chinese calligraphy as part of Howard’s World Languages Day. “My education was like everyone else’s. We didn’t study the normal courses; we were doing the political things. We spent a lot of time in the countryside and in the factory to be reformed.” It was only “after I learned English [that] I realized that Chinese, my own culture, was just as important. So this coming to America to teach about Chinese culture is really my journey to return to my roots,” Li said.

Roberson has arranged to send a group of Chinese language students to a summer immersion program at Soochow University in Suzhou, China, in 2006. That partnership grew out of an American Association of Community Colleges conference that he attended in 2004, where he made contact with three institutions interested in opening their doors to U.S. students. Soochow offered the best deal—tuition and room and board for a month for just $750—and Roberson returned to China this spring to finalize the arrangement. A new community college in Shanghai is hoping to form a partnership with Howard’s English Language Institute and develop an international business and marketing course that Howard could cosponsor in Shanghai. Again, as he did in Denmark, Roberson looked for ties that were practical and that two institutions 7,400 miles apart could manage on their own. “You don’t want to go to China without knowing what you’re doing because you can do a lot of toasting and bowing and come back with nothing,” he said.

Countering Trends: Growth in ESL

Howard’s English Language Institute has grown in the past four years even as similar programs on many U.S. campuses have seen enrollments slump due to visa restrictions and increased competition from other English-speaking countries. The English Language Institute started with six students in 2001; this year it enrolled 90, including 77 international students on F-1 visas and 13 permanent residents. The intensive instruction—typically 18–20 hours per week—is geared for those interested in boosting their English proficiency as rapidly as possible. The institute can custom-tailor courses to a student’s particular interests and needs, as it did for June Eun Song, an aspiring artist from Korea, who after three semesters at the institute won a $30,000 scholarship to the Cleveland Institute of Art.

The institute is just one part of Howard’s large, robust English as a Second Language program, which enrolls 1,400 non-native speakers—mostly permanent residents of Howard County who are part of a growing population of immigrants from Korea, Latin America, and other parts of the world—in noncredit courses, and 400 others taking the same classes for academic credit. The noncredit and credit work closely together with a wide range of students who need better English skills, from professionals with advanced degrees to blue-collar workers. Some students are readying themselves to matriculate at Howard or four-year colleges; others already possess a college degree but are preparing for graduate school at Johns Hopkins University and other top institutions.

An Action Plan for Continued Growth

Howard Community College’s internationalization proceeds apace on multiple fronts: a rapidly growing English Language Institute; more opportunities for students to study abroad and more teacher exchanges; support for faculty to deepen or develop international expertise; and an entrepreneurial continuing education division that casts a wide net for training opportunities. Its journey is far from complete. It is just beginning to consider how to implement the charge it received from a citizen’s Commission on the Future “to make a clear and visible strategic commitment to international/intercultural competence.” A Multicultural Plan Committee headed by Kate Hetherington has produced a blueprint that includes stepping up international requirements, more faculty exchanges, and, if and when dorms are built, expanding the Multicultural Center and opening a “world café” for people to meet, eat, and exchange ideas and experiences. With Beckie Mihelcic phasing into retirement—she handled the international duties parttime in addition to teaching—Howard has hired as the first full-time director of international education George Barlos, an attorny who formerly directed international programming and study abroad at the University of Dayton and Tulane University. It also hired a fulltime assistant, Christele Cain, who holds twin degrees from Howard in graphic design and mass media web production.

2005 Comprehensive Colgate University

The origins of Colgate University’s elaborate array of off-campus study programs can be traced not to London or Paris or Venice but to Washington, D.C., where the liberal arts college dispatched a professor and handful of students during the Depression to see for themselves how President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his New Deal were reshaping the executive branch. The trip became a regular feature of Colgate’s political science program: while the Hamilton, New York, campus was still deep in winter’s grip, a faculty member would lead a contingent of juniors or seniors south to deepen their understanding of the U.S. system of government, often with Cabinet secretaries, leaders of Congress, and other senior officials serving as docents.

Education Abroad is Part of Colgate’s Character

Colgate earned the distinction of becoming the first of many U.S. colleges and universities to offer a semester in Washington; the program observed its seventieth anniversary in 2005. The private undergraduate institution sitting squarely in the rural middle of New York State saw that this model of sending a professor and students away for 12 weeks to teach, study, and learn together could be applied equally well in more distant parts of the world. In the 1950s, a study group headed off to Argentina. Later came study groups to Europe and Asia. Today this modest-sized institution (enrollment: 2,750) offers up to a dozen Off-Campus Study Groups each semester around the globe, from London and Madrid to Chennai, India, and Wollongong, Australia.

Ten percent of the 267-member Colgate faculty venture off campus each year with Study Groups or on briefer Extended Study Groups, which allow students to see the places they studied in Hamilton, from the back alleys and markets of modern Beijing to excavations in Rome and Pompeii. A Colgate professor teaches one or two courses to the study group, typically 14 students, and the students take two or three more at local universities or from scholars that Colgate engages locally. By the time they carry flaming torches around Taylor Lake on the night before graduation, upwards of 70 percent of Colgate’s seniors have had one or more international study experiences. The emphasis on the international is engrained deeply today in Colgate’s character.

The off-campus study groups represent “an incredible commitment by the faculty,” said President Rebecca Chopp, a religion and American culture scholar who has led Colgate since 2002. One hallmark of this type of liberal arts education is close faculty-student engagement, she said, “and there is no greater place for that than a study abroad program.”

“So many students come back intellectually alive in a way we have never seen,” said the former provost at Emory University and dean of Yale Divinity School. Chopp knew before arriving in Hamilton that Colgate students studied abroad in large numbers, but had not realized “that so many went on Colgate’s own programs—and that so many faculty went with them.”

A Very Involved Faculty

“After spending my whole career in bigger places, I’m amazed at the kind of education students get here, the opportunities for interaction with faculty, and the way faculty think about the students all the time,” said Chopp. It demonstrates that “our faculty really understand that for the twenty-first century, we simply have to find ways to ensure that each student understands the world.

The Colgate approach also affords faculty many opportunities to become “truly global scholars,” she said. “I have long thought that getting faculty to live abroad is as important as getting students to live abroad.”

Nearly 250 Colgate students—mostly juniors—spent a semester abroad in 2004–2005, and almost half that number ventured out in January or after the end of regular classes in May, to destinations that ranged from Mayan Mexico to Zambia to Hiroshima. One hundered others studied abroad on non-Colgate programs. A glance at the organizational chart for the Office of Study Groups/International Programs underscores how much Colgate relies on faculty for the success and breadth of its study abroad programs. The small office is led by Director of International Programs Kenneth J. Lewandoski, and Assistant Director Jennifer Durgin, who taught in Toulon, France, as a Fulbright scholar after graduating from Colgate in 2000. A study abroad adviser and a secretary round out the four-person Off-Campus Study staff.

Faculty members bear extensive responsibility for making these far-flung programs work, not only while abroad with the students, but also during preparations beforehand and follow-up afterwards with students they mentored. With the exception of language instructors, most Colgate faculty who lead study groups are tenured; some are veterans of a half-dozen or more study groups, and there is usually no shortage of volunteers. Faculty invariably describe the experience as physically exhausting but intellectually invigorating, and students and alumni say that the bonds formed with professors and classmates while studying abroad were by far the strongest from their days at Colgate.

Mary Acoymo, 20, a junior from Redondo Beach, California, who went on the London Study Group in Fall 2004, said, “We all became like a family abroad, although at the same time we definitely did grow independently. That was really nice—to feel taken care of, but also unleashed.”

Chopp said that when she visits alumni and asks with whom they stay connected at Colgate, they’ll respond, ‘Well, my four best friends are people I studied abroad with.’ Some more recent grads will say, ‘I married (someone) from my trip.’”

Strategic Thinking Yields Results

Match-making isn’t one of the purposes of Colgate’s Off-Campus Study, but study abroad is an integral part of the Colgate experience. Early in Chopp’s tenure the administration, faculty, and trustees mapped a strategic plan with three main goals:

- To impart the classic liberal arts skills of communication and critical thinking in ways that reflect 21st-century challenges and opportunities;

- To multiply connections between faculty and students especially in joint research and scholarship; and

- To instill civic character building on Colgate’s strong sense of community, locally and globally.

Colgate received 8,000 applications—easily a record—for the Class of 2009; it had to turn down almost three-quarters of them. Chopp believes the study abroad programs fueled the 22 percent spike in applications. “For many parents and students, the notion that you can actually go study with a Colgate professor in a way that will contribute to your major is very attractive,” she said.

International Student Population is Growing

More than 1,000 of those applications came from international students recruited by Colgate from around the globe through the generous provision of financial aid and scholarships. The contingent of international students on the Hamilton campus numbers more than 150; these students comprise 5 percent of enrollment, a 50 percent increase in five years. With room, board, and tuition at Colgate topping $41,000 a year and with a finite amount of financial aid, the competition among international students for a place in the freshman class is intense.

“They are incredible students and they are heavily invested in campus life,” said Senior Assistant Dean of Admissions Gregory B. Williams, who has made recruiting trips across Asia and other continents. The valedictorian and the salutatorian of the Class of 2004 were from Shanghai, China, and Sofia, Bulgaria, respectively. Kayoko Wakamatsu, an assistant dean of the college who advises international students, said, “We have an amazing number of students from Bangladesh and Bulgaria, and several from Nepal. We have students here who you might not suspect would want to come to farmland in the middle of New York.” The international students welcome the individualized attention they receive from faculty and administrators. “Students tell me repeatedly that they have opportunities here that they cannot imagine having elsewhere,” said the Japanese-born Wakamatsu, who was raised and educated in the United States.

An ‘Elegant and Elaborate’

Core Curriculum If a sense of remoteness provided early impetus for the pioneers of Colgate’s study groups, the faculty now is motivated more by a recognition of what Mary Ann Calo, associate dean of the faculty and professor of art, calls “the responsibility of educators to engage with the world.”

“We are in a somewhat isolated location, but we are definitely not a provincial faculty. It’s a very worldly group,” said Calo. “This enters our curriculum in ways that don’t necessarily require students to leave campus. We are encouraging them to think about the world here. We obviously encourage study abroad and have great participation, but we are also dealing here with a very dynamic curriculum intent on engaging with the world in a lot of ways, on a lot of levels.” Even those without a passport will “get at least some sense of culture, social systems, religion, and art outside the West,” Calo said.

The core curriculum, which dates back to 1928, is another signature feature of a Colgate education. It not only requires study of Western and non-Western civilization, but encourages interdisciplinary studies—an aspect that has made the faculty more international both in its research and its mien. Students can choose from nearly two dozen core courses in non-Western culture, from Core Mexico and Core Japan to the Black Diaspora to the Iroquois. (The core also requires several courses on Western civilization, the roots of modernity, and scientific perspective.) “It’s one of the most elegant and elaborate cores in the country,” said Jane Pinchin, former provost and dean of the faculty and professor of English since 1969. The emphasis on interdisciplinary study allows smaller departments from anthropology to classics to physics to hire more faculty than if their professors were teaching only in their field. “You can maintain goodly numbers who are teaching not only in their specialties but also in the core. It really develops a very international faculty,” said Pinchin, who served as interim president in 2001–2002.

A Campus with Personality Makes a Good Neighbor

“We talk about the Colgate DNA, that we have a real kind of personality,” said Chopp. “It takes different shapes, forms, and sizes and colors”, but there is a kind of extroverted, robust, [and] very, very curious personality. We have an incredible campus life built by the students largely, not by the staff. We attract lots of people who are athletic. It’s hard to walk on this [hilly] campus if you’re not into fitness. Some of that is the Division I [sports] program, which most of our peers do not have; some is an enormous outdoor education program and every club sport you could imagine. We just started a cricket team.”

“We’re very good at building community,” said the president, who added with a smile, “In a rural context, students learn that skill whether they like it or not, because there is nothing else to do.” But Colgate takes community-building seriously, and the results can be seen clearly in Hamilton. The university engineered a $15 million redevelopment that breathed new life into the village a few years back. Colgate even moved its bookstore a mile off campus to anchor a cluster of shops thriving inside refurbished, red brick storefronts, overlooking the tangle of roads that converge on the quaint Village Green.

As a young sociology professor, Adam S. Weinberg, played an active role in the redevelopment process and in getting hundreds of students involved in service learning projects in Hamilton, across Madison County and beyond, including Utica, home to more than 10,000 Bosnian refugees. He helped students launch nonprofit organizations and microenterprises. “It was a fantastic time for somebody like me to be here,” he said. In 2001, Weinberg, now vice president and dean of the college, and three student activists formed the Center for Outreach, Volunteers and Education (COVE) to provide a permanent base of operations for Colgate’s service learning activities.

“We don’t do community service at Colgate. COVE is our center for social entrepreneurship,” said Weinberg, who is responsible for all of the education and activities that take place outside the classroom. We’re interested in teams of students coming together and partnering with other people to solve problems, to make the world a better place.” The university gave COVE prime space and a fulltime staff on the first floor of East Hall, one of the oldest dormitories on campus. Weinberg also helped Adonal Foyle (the center for the Golden State Warriors of the National Basketball Association and a 1998 magna cum laude Colgate graduate) launch Democracy Matters, a national nonpartisan group that encourages young people to work to limit the influence of big money on politics.

Weinberg called Colgate, “a model for how you blur the lines between academics and student affairs.” Weinberg and his staff encourage students to talk “across difference” and work out disputes democratically, whether debating the volume of a roomate’s stereo or how to run one of the 130 student organizations on campus. They teach strategic planning to students in the Colgate’s themed housing units. The university also has purchased the houses of fraternities on campus with an eye toward exerting greater influence on that side of residential life. It was built spacious townhouses for groups of 12 to 16 students and gave room bid priority to those with a special theme or purpose for living together, including those coming back from study abroad. “We’ve purposely built the townhouses big enough so they can have parties and introduce other students to the music and culture” that became part of their lives, the dean said. “It’s our hope they will continue the conversations.”

“A study group that comes back from India comes back fundamentally transformed. Those students come back thinking differently about themselves, about the liberal arts, about their relationship to the world around them. How do we capture all that energy and enthusiasm back on campus?” said the dean. “What happens on too many campuses is those kids come back changed, and then they isolate themselves and just wait until they graduate. We’ve worked very hard to make sure that doesn’t happen at Colgate,” Weinberg said.

The COVE has helped returning students continue community service projects they began while on Extended Study trips to South Africa and the former Soviet republic of Georgia, and it arranges summer internships with nongovernmental organizations in developing nations. The debate team went to Malaysia last December to compete in the world championships, and the rugby team has toured Ireland and England.

The COVE Model, “is important because it takes our intellectual capital as well as civic responsibility outside the classroom and the campus. Education was founded with three missions: research, teaching, and serving the public good. The COVE combines all three in a powerful way, “ Chopp said.

And that cricket team the president mentioned? It was started in large measure thanks to the passion for the sport that Christopher Burns ’05 of Silver Spring, Maryland, acquired while on a 2003 study group in Chennai, formerly known as Madras. Burns donated 200 pounds of cricket bats, balls, pads, and other gear to the university. Last summer Colgate built its first cricket pitch.

Looking Forward

A campus committee is exploring how to reach the 2003 strategic plan’s ambitious goals for further internationalization. No thought is being given to retrenchment. Dean of the College and Provost Lyle D. Roelofs, a physics professor who came to Hamilton in 2004 after two decades at Haverford College, said, “For this experience to have the maximum impact on Colgate students, we are constantly mindful of increasing the opportunities in the less well traveled parts of the world, not to the exclusion of the popular places to go.”