2009 Comprehensive Portland State University

The motto of Portland State University in Oregon is emblazoned on a sky bridge that spans Broadway, Portland’s main thoroughfare: Let Knowledge Serve The City. “We’d like to change it now to Let Knowledge Serve the Globe,” quips Kevin Kecskes, associate vice provost for engagement. Portland State, already known for deep community partnerships, today works on a broader canvass seeking sustainable solutions to economic, environmental, and social challenges that confront cities everywhere.

This urban university practices what it preaches. In a city crisscrossed by light rail and streetcars, most students, faculty, and staff walk, ride bicycles, or take public transportation to the compact, 49-acre campus. The new president, Wim Wiewel, an expert on urban affairs, rode a bicycle to work on his first day in August 2008. Most of the 26,000 students commute; the dorms abutting Broadway house only 2,000 of them, although plans are on the drawing boards for several thousand more.

The city itself is a powerful draw for the 1,700 international students. “Typically international students want to come to an urban environment. The living environment is more supportive culturally and more diverse than in a university town like Corvallis or to an extent Eugene,” said Gil Latz, vice provost for international affairs and a professor of geography. Portland’s lures also make faculty recruiting easier. “A lot of people want to live in the Pacific Northwest,” said Ronald Tammen, director of the Mark Hatfield School of Government. Wiewel, who came from Chicago, said his new hometown “is such an easy city to sell. It’s a great brand.”

Wiewel is building on momentum created over a decade at Portland State. His predecessor, Daniel Bernstine, doubled enrollment and won the National Association of State Universities and Land-Grant Colleges’ (now the Association of Public and Land-Grant Universities, A·P·L·U) Michael Malone International Leadership Award in 2005 for his efforts to internationalize Portland State.

Broadening the Experience of ‘New Majority’ Students

The new president, a native of Amsterdam, views attracting more international and out-of-state students as a strategic way of broadening the educational experience for Oregon students. The student body typifies what some call “the new majority” in American higher education: older and often part-time. Most of these collegians “can’t park their family and their job for six months to go study in Berlin,” said Duncan Carter, associate dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

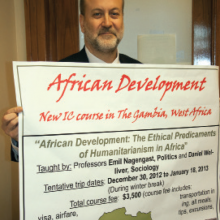

Fretting over that reality would be pointless, said Provost Roy Koch, so instead Portland State has concentrated on offering short, faculty-led education abroad opportunities, often over spring break as part of longer courses. The number who study abroad is still modest (541 in 2007–08) but it has been climbing. Ron Witczak, assistant vice provost and director of education abroad, said, “We started in 2001 with three or four faculty-led programs and roughly 30 students. Now we’re up to 27 with close to 250 students.” Last year a full-time coordinator was hired. “There’s no place-bound student who can’t figure out a way to go abroad for two weeks if they want to,” said Wiewel. Both the length and cost—typically $2,500 to $3,500—make the short-term programs attractive, and partial scholarships are available for those in need.

“There’s no place-bound student who can’t figure out a way to go abroad for two weeks if they want to.”

Jill Scantlan, who quit school, earned a GED at age 16, and became a licensed massage therapist, spent nine months studying in Hyderabad, India. The 25-year-old international studies major aims to earn a master’s degree and return to India to do public health work. Helen Johnson returned to college for a master’s in teaching English as a second language after two decades as a homemaker. The two summers she spent practice teaching in South Korea were “the experience of a lifetime,” said Johnson, 47, a native of Greece who aspires to teach English to immigrants. “Now I’m back to what I really want to do.”

Emphases on Sustainability and Community Learning

Sustainability was the watchword at Portland State, even before it received a 10-year, $25 million matching grant in 2008 from the Miller Foundation—the largest gift in the institution’s history—to make the university an exemplar of sustainability, from the curriculum to campus life to community partnerships. Wiewel said, “You can’t be known across the world for everything unless you are Princeton or Harvard or some place like that. We’ve got to pick our strengths, and sustainability is one of those. It’s not just green wash; it’s real. People are doing it.” Portland State is working with Hokkaido University in Japan and Tongji University in China on ways to foster sustainability, and the issue drives the curriculum for the Hatfield School’s executive leadership and training programs for hundreds of government managers and business executives from Vietnam, Japan, and South Korea.

Portland State’s long-standing relationship with Waseda University in Tokyo also focuses in part on sustainability. The campus houses the Waseda Oregon Office, which brings dozens of Waseda students to Portland each year and sends 60 students from across the United States to Tokyo each summer for intensive Japanese classes. Latz, who studied at Waseda as an Occidental College undergraduate, is looking for a third partner elsewhere in Asia for a three-way exchange around the global sustainability theme. “We have to move away from thinking only in terms of two dimensions to a problem,” the geographer said. “If this third country were Korea, for example, the students would learn that the Korean approach to sustainability would be very different from the Japanese approach and the Portland approach.”

Community-based learning is also a key to the curriculum at Portland State, where all undergraduates are obliged to perform service. Eight thousand students work in teams to identify and address community problems each year, and “we are incorporating this service element into our study abroad programs,” said Latz.

Kecskes, who directs the community partnerships, eschews the “service learning” term. “Community-based learning is a much larger umbrella. ‘Service’ can connote a one-way street,” he said. One course that Kecskes helped design takes students to Tucson, Arizona, and Nogales, Mexico, to study immigration policy and pollution from global factories south of the border. Instructor Celine Fitzmaurice’s students spend a night in a migrant shelter and live with families who work in those factories. Often, she said, there is at least one student whose parents entered the U.S. without documentation. Kecskes designed another course in which students meet with leaders of Portland’s Oaxacan immigrant community before heading to Oaxaca, Mexico, to see conditions there for themselves.

Portland State is also the new home of the International Partnership for Service Learning & Leadership, a not-for-profit that runs programs for undergraduates’ combining study abroad with volunteer service. It will offer a master’s degree in international development and service that includes six months of courses at Portland State and six months’ service in Kingston, Jamaica, or Guadalajara, Mexico.

Surprises in Studying Impact of Education Abroad

Portland State participated in the Global Learning for All project of the American Council on Education (ACE), which looked at how institutions with large numbers of nontraditional undergraduates—adults, minorities, and parttime students—incorporated international content and activities into their curricula and campus life. Portland State also shared a Fund for the Improvement of Postsecondary Education grant with five other institutions to measure the impact of international learning on students’ attitudes.

“It was as though the (Russian) language had disappeared,” said Freels, but now enrollments have rebounded partly with the help of a $1 million National Security Education Program grant.”

Carter, associate dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, Latz, and Patricia Thornton, an associate professor of international studies, helped pilot a test that examined what students took away from their education abroad experiences. “We got some surprises,” said Carter. “Students who had traveled frequently abroad or indicated several short trips abroad outside of an academic context actually scored lower on the attitude section than students who’d never left the country.” He added, “We call this the Club Med experience and hypothesize that this may actually do more harm than good.”

The faculty senate, after lively debates over the wisdom of expanding the list of core objectives for a Portland State education, recently adopted an international learning outcome as part of a broader revamping of curricular requirements. The new goal reads: “Students will understand the richness and challenge of world culture, the effects of globalization, and develop the skills and attitudes to function as ‘global citizens.’” Provost Koch said, “It was implied before, but now it’s very explicit.” The challenge is figuring out how to accomplish it for engineers as well as history and international studies majors. “We don’t want to just create another course or set of courses. We want to make it an integral part of students’ existing coursework,” he said.

Luring Students to Russian Language Classes

Four thousand Portland State students took foreign language courses in fall 2008. “We are the largest unit in the university,” said Sandra G. Freels, chair of the Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures and professor of Russian, one of 20 languages taught. When the Soviet Union collapsed, “it was as though the (Russian) language had disappeared,” said Freels, but now enrollments have rebounded partly with the help of a $1 million National Security Education Program grant.

That grant allowed Portland State to offer 22 Russian-speaking freshmen and sophomores the opportunity last fall to add an extra, two-credit class taught in Russian to the standard, six-credit Inquiry course, one of the university’s requirements. These students were encouraged to live on the Russian immersion floor of a dorm and later might spend a full year at St. Petersburg State University. The purpose, said professor Patricia Wetzel, “is not aimed at producing Russian majors. It’s producing chemistry, business, and history majors who can use their language professionally.” The students, many of them heritage speakers of Russian, often “had no idea what their language skills are worth,” said Freels.

Raising the Research and Global Profile

In bringing Wiewel to Portland, the State Board of Higher Education chose a president whose most recent book was Global Universities and Urban Development. Wiewel first came to the United States from Holland on an American Field Service high school exchange. After earning a doctorate in sociology at Northwestern University, he directed the Great Cities Institute at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and was provost of the University of Baltimore in Maryland. His goal is to double the externally funded research budget to $80 million in five or so years. Research “by definition nowadays is global…. The more you raise the research profile, the more it allows you to go beyond your local focus,” Wiewel said.

The Hatfield School of Government has taken an entrepreneurial approach to growing its international profile. “We have tentacles that stretch throughout the local community, the state, the nation, and the world,” said Tammen, the director. “We grow not on public money, but on money that we generate ourselves by training government officials in the United States and abroad and by doing contract work for a lot of different folks.”

Marcus Ingle, director of the school’s International Public Service & Fellows program, regularly takes Portland State students to Vietnam and recently won two grants from the Ford Foundation to establish a program on state leadership for sustainable development at the Ho Chi Minh Political Academy in Hanoi. He also had a hand in arranging a $2 million Intel Corp. initiative that has brought 28 Vietnamese engineering students to Portland for two years to finish their studies and earn a Portland State degree.

“We grow not on public money, but on money that we generate ourselves by training government officials in the United States and abroad and by doing contract work for a lot of different folks. ”

Political scientist Birol Yesilada, chair of contemporary Turkish studies, and Harry Anastasiou, a professor of conflict resolution, take students to Cyprus for two weeks each year to study life on both sides of the Green Line that divides the Greek and Turkish communities. Yesilada said Portland State is still “a young campus. It does not have entrenched rules. It doesn’t have the financial means of a Harvard, but if you have a good idea, you’ll get support to do it. They are not going to stand in your way.”