2016 Spotlight University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s (UNC-Chapel Hill) relationship with the Universidad San Francisco de Quito (USFQ) in Ecuador started in an Amazonian jungle. Biology Professor Stephen Walsh first met Carlos Mena, who would become his PhD student and then later join USFQ as a professor, during a research trip to Ecuador in the late 1990s. Their personal relationship paved the way for a comprehensive partnership between their two institutions that culminated in the establishment of the Galápagos Science Center in 2011. UNC-Chapel Hill’s relationship with USFQ has subsequently expanded to include interdisciplinary research, student and faculty exchange, and community engagement, much of it focused on developing local capacity in the Galápagos Islands.

Building Strategic Partnerships

UNC-Chapel Hill’s collaboration with USFQ is characteristic of its larger approach to internationalization. According to Katie Bowler Young, director of global relations, UNC-Chapel Hill has chosen to focus on creating deep relationships that span multiple disciplines and ultimately result in engagement with local communities.

“Our key partnerships were established through faculty-to-faculty connections. Partnerships grow to include additional faculty, departments, and areas of study. Our team from UNC-Chapel Hill Global then helps develop partnerships, trying to extend them into new areas,” she says.

UNC-Chapel Hill’s long-term engagement in Ecuador was born out of Walsh’s and Mena’s joint research in the Galápagos, which Walsh first visited in 2006 as part of a project with the Galápagos National Park and the Nature Conservancy. “I continued to go back and forth to the Galápagos trying to understand their local needs, but to also begin to develop a UNC vision of what a long-term commitment in the Galápagos might look like,” Walsh says.

USFQ was interested in trying to identify a partner in the Galápagos to expand from undergraduate teaching to a more comprehensive research mission. “For us, we needed to make our presence in [the] Galápagos stronger. We needed an ally for that,” Mena says.

Infrastructure as Key to Sustainable Research

According to Walsh, the two institutions jointly identified infrastructure development as key to creating a sustainable research program in the Galápagos, which he says often suffers from a “one-and-done mentality where people go, gather data, write papers, and go home.”

“What we wanted to do is break this traditional approach to research and create something that is more connected to the needs of the Galápagos. Usually, research is done by foreign scientists who come to the Galápagos, and take their results with them when they leave. We wanted to change from that to something that is growing up from the community,” Mena adds.

In addition to discussing student mobility, they decided that there was a need to build a physical structure as the core of the collaboration between the two institutions.

“If we could build the Galápagos Science Center (GSC) and equip it with needed laboratories, providing unique capacity for science and education in the Galápagos, that would be the basis for an important increase into understanding the social, terrestrial, and marine subsystems in the Galápagos,” Walsh says.

It took almost five years from the time when UNCChapel Hill and USFQ first signed a general memorandum of understanding in 2007 to when the center opened its doors in 2011. Although UNC-Chapel Hill cannot legally own property in the Galápagos due to Ecuadorian law, the funding and construction were equally shared between the two institutions. More than 50 faculty members have subsequently been involved in the partnership.

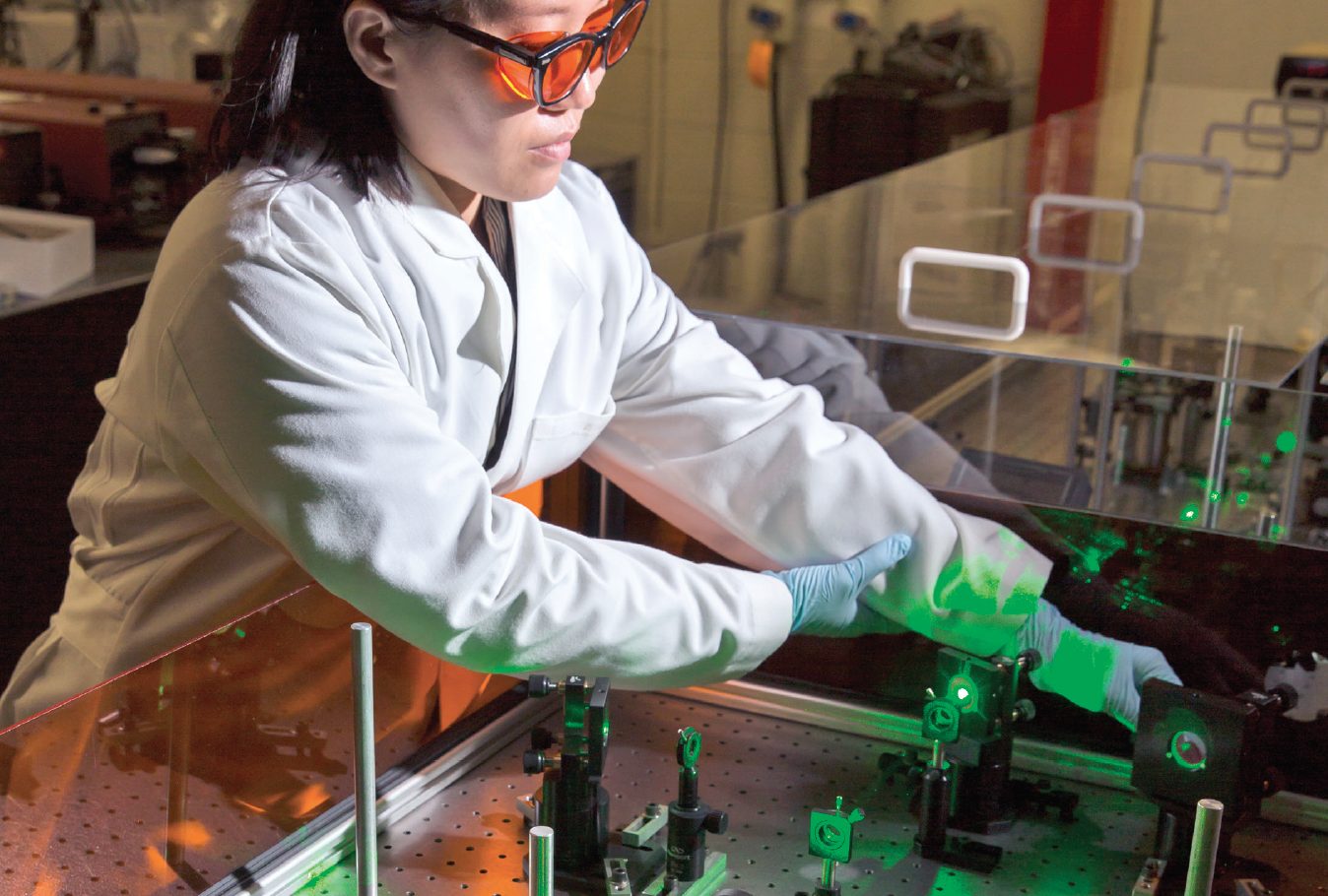

Having a local base has made research easier for visiting faculty. Diego Riveros-Iregui is a physical geographer in the emerging field of ecohydrology— “where life and water intersect,” as he puts it. He has spent time at the Galápagos Science Center studying the relationship between water, plants, and soils in tropical regions.

“I have been working in the tropics for several years and have run into many of the same challenges that everyone faces: customs, permits, maintenance of equipment, data collection, sample preservation, etc. When the opportunity to work in the Galápagos came up, working with the staff at the GSC facilitated many of the aforementioned challenges, giving me time to focus on research,” Riveros-Iregui says.

Human and Ecological Systems Meet in the Galápagos

Mena says that scientific research in the Galápagos has traditionally been focused on hard science in areas such as botany, zoology, and evolution. From the beginning, they wanted to position the Galápagos Science Center as an interdisciplinary hub.

“The Galápagos are oftentimes thought of as Darwin’s paradise. But when you’re there, you can’t help but understand that the environment is changing and interacting with people, and shaping their behaviors,” Walsh says.

He adds that it was evident they needed to involve social sciences: “Two hundred twenty-five thousand tourists came to the Galápagos in 2015. About 30,000 residents live in the Galápagos Islands on four populated islands. It’s clear that it’s not just about ecology. It’s about the connection of people and ecology.”

Maya Weinberg is a Latin American studies and political science major who took a gap year from UNC-Chapel Hill to do an internship at the GSC. She worked with Walsh on a project using global information software (GIS) to map out human development on San Cristóbal. She was involved with mapping buildings and putting together a report on infrastructure development.

She says that the interdisciplinary nature of the work at the GSC—and the opportunity to be involved in multiple projects in multiple fields—allowed her to make connections she wouldn’t otherwise have made: “With my experience working with human development, conservation, as well as geography I have become increasingly interested in policy and politics, as these are the disciplines that connect all three.”

The Importance of Engaging with the Local Community

Mena says that they built the center with the goal of providing more information to local communities and politicians to make informed decisions on issues such as health, tourism, infrastructure, and economic development.

He says that members of the local community are included in the research process. They work with a community board that keeps the GSC informed of local interests, and have close partnerships with Galápagos National Park and the local government council in order to find better ways to protect the islands.

UNC-Chapel Hill is currently engaging the community in the area of health. A new hospital was recently built on San Cristóbal, and representatives of both UNC and USFQ met with the director of the hospital and the ministry of health for the Galápagos. In 2016 the UNC-Chapel Hill School of Nursing sent a delegation to USFQ in Quito and to the Galápagos to visit the new hospital.

GSC also keeps the community informed about the results of its ongoing research. Kelly Houck is a biological anthropologist and UNC PhD candidate who studies human health. As part of her fieldwork on San Cristóbal, she collected samples of tap water to test for contamination as well as took blood, urine, and fecal samples from local residents to measure different health impacts.

“The water samples needed to be tested within 24 hours of collection and because of GSC infrastructure, we were able to give the results back immediately to the households and provide suggestions for treating contaminated water, such as boiling or using bottled water for drinking,” she says.

“In addition, we were able to provide them with preliminary results from their blood and urine test for indicators of infections, and advise them to seek further free testing at the hospital on San Cristóbal,” she adds.

Young adds that it is not only the local community in the Galápagos that benefits from the partnership. UNC-Chapel Hill’s undergraduate students have also been able to participate in opportunities through the partnership. In addition to semester or year-long exchanges to USFQ, undergraduates can also take advantage of faculty-led summer programs.

Billy Gerhard graduated in 2014 with a bachelor’s in biology and then earned a master’s of science in public health in environmental sciences and engineering. As an undergraduate, he did a summer program at the GSC in 2012. The next summer he returned as a winner of the Vimy award, a grant of up to $15,000 given annually to an interdisciplinary team of students working collaboratively to pursue research or service projects outside the United States. He is currently pursuing a PhD in environmental engineering at Duke University.

“The project definitely impacted my career trajectory. Working abroad required me to plan ahead, anticipate problems, organize contingencies, and communicate effectively. These skills are useful in any career and the opportunity to practice them was invaluable,” he says.

“I am currently writing the results of my research on drinking water in San Cristobal for publication,” he adds.

UNC has also sent local K–12 and community college educators to the Galápagos through its World View program, which strives to help teachers give their own students global competency. “We’ve seen this partnership benefit those beyond our campus as well,” she says.

Young says that having faculty members who are deeply committed to the local community has been key from a partnership development standpoint.

“It couldn’t have happened without two institutions that wanted it to happen, and two leaders, Carlos and I, who saw a vision, transmitted it to other faculty and students, and moved forward with a program that would be committed to community outreach, education, and research at a marvelous place,” Walsh adds.