2006 Comprehensive Earlham College

Many liberal arts colleges and universities founded in colonial times and the century after U.S. independence jettisoned their founders’ religiosity, but not Earlham College. Earlham is the proud bearer of a Quaker heritage in Indiana that began after farmers who could no longer abide slavery migrated from North Carolina to the Northwest Territory in the early 1800s. Soon the Quaker population of Richmond, Indiana, rivaled Philadelphia’s. The Indiana Friends in 1847 established a boarding school that a dozen years later became Earlham College—named for the home of a prominent Quaker minister in England and pronounced with a silent h (like Durham).

Earlham is still imbued with Quakerism. The 100-member faculty makes decisions not by vote but by seeking consensus on issues small and large. Their biweekly meetings in unadorned Stout Meetinghouse are led not by the president or deans, but by a clerk of the faculty chosen by his or her peers. President Doug Bennett also presides over a Quaker seminary, the Earlham School of Religion. Upwards of a quarter of the faculty and 15 percent of the students are Quakers, although those are only estimates. Len Clark, provost and academic dean, once tried to count the Quakers on the faculty for the board of trustees. “But when you say, ‘Now, are you actually a Quaker?’ Quakers tend to answer not ‘Yes’ or ‘No,’ but ‘Why would you want to know that?’” Clark said. “It’s sort of like the Heisenberg uncertainty principle: The numbers change if you try to count them. I gave up.”

A former president, Tom Jones, once described Earlham as “a cross between a Friends meeting and a scientific laboratory.” It sends graduates in large numbers on to Ph.D.s in biology, the life sciences, and sociology, as well as other fields. The number of languages it teaches is not extensive, but large numbers of students achieve proficiency in Spanish, French, German, or Japanese. It recently added classes in Arabic, and offers Latin and ancient Greek as well. Every student must demonstrate command of a second language as a prerequisite for graduation.

The newest major is Comparative Languages and Linguistics, requiring advanced study in at least two languages and study abroad. It is an institution engaged in what Bennett calls “a full court press on internationalization,” from the emphasis on study abroad to international material threaded throughout the curriculum. “It’s not just in the French department and the history department, it’s everywhere,” said Bennett.

Earlham boasts a daring array of semesterlong study abroad opportunities that entice most of the 1,200 undergraduates to other parts of the world. To this experience some students add a May term. Earlham offered a semester-long program in Jerusalem from 1982 to 2000, when strife in the Middle East and a State Department travel advisory forced it into hiatus; the college hopes to restart the program in Amman, Jordan. Civil unrest also forced Earlham to relocate a signature program from Kenya to Tanzania in 20032004. Other off-the-beaten-path study abroad choices include:

-

Northern Ireland. An exploration of the long religious and social conflict in Northern Ireland. Students stay with families in Belfast and Derry and learn the history of “the Troubles” as well as the politics and culture of the six Ulster counties that remained under British rule when the Republic of Ireland gained independence in 1921.

-

U.S.-Mexico Border. Students electing this program, located in the neighboring cities of El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, are immersed in learning how such critical issues as immigration, free trade, human rights, and the environment play out in the border region.

-

South Asia. Launched in 2005, this ambitious program takes students to Chennai, India, and Kandy, Sri Lanka, to study economics, culture, and conflicts on the subcontinent.

-

Japan. Studies in Cross-Cultural Education (SICE) program sends students each fall to study Japanese at Iwate University in Morioka and assist in local middle and high school English classrooms. Upon graduation, many SICE students return to northern Japan as assistant English teachers. Earlham’s program served as a model for the Japan Exchange and Teaching (JET) Program.

More than 70 percent of Earlham students study abroad. All must fulfill requirements in domestic and international diversity, and Earlham’s 45 majors and minors include more than a dozen interdisciplinary programs, from Peace and Global Studies to Latin American Studies to minors in Jewish Studies and in Quaker Studies.

Patricia Lamson, director of the International Programs Office, credits faculty curiosity with helping grow Earlham’s garden of international offerings. “They like to create and do with students, because we are a teaching college. Teaching is our priority,” said Lamson. A change in the academic calendar seven years ago left room for a mini-term in May. Faculty quickly realized they could take these classes overseas “and—boom!—just like that, it exploded,” she said. “They range from studying Papiamento in Curacao to weaving and arts in Turkey.” Her husband, Howard Lamson, a professor of Spanish, inaugurated Earlham’s semester-long study abroad program to Mexico back in 1972. Now the faculty couple take students each May to Cuautla, Mexico, for immersion classes at an Earlham-owned facility called Casa Sol. They also work with students who spend a semester there or in the border program.

Music professor Dan Graves was a junior faculty member when he showed up in Lamson’s office in 1987 and volunteered to lead the spring semester in London. “Patty laughed and said, ‘The waiting list is six years. But have a seat and tell me: If you could go anywhere in the world and lead a program, where would it be?’” recalled Graves. “I had never been out of the United States, but I’m a musician so I said, ‘I’d like to go to Vienna.’”

He led the first choral group to the Austrian capital in 1988 and has since taken Earlham’s sopranos, altos, and baritones half a dozen times to study German and sing in the city’s great cathedrals. “Why anybody would trust somebody who had spent the last 13 years teaching in a small high school in Connecticut to get something going in Vienna is beyond me. But there’s that kind of trust,” said Graves.

Earlham’s Kenya program was begun in 1978 by a couple in the biology department. Another faculty couple, Brent Smith—professor of biology—and Nancy Taylor—an assistant professor of art and reference librarian—inherited the mantle and have taken students to Kenya five times and to Tanzania once for full semesters. Smith also has led students to the Galapagos and Ecuador, and Taylor has taken a May class to Turkey to study weaving. Their two sons grew up accustomed to spending every third autumn in Africa. When the boys reached high school age, “I remember asking them, ‘Do you guys want to go back?’” Taylor said. “The answer was, ‘Oh, yeah. That’s what makes our family cool.’”

Sara Penhale, science librarian and associate professor of biology, is also a seasoned Africa hand, having led Earlham students to Kenya and Tanzania four times and organized multiple safaris for alumni and others. Her husband, Allan M. Winkler, a Distinguished Professor of History at Miami University in Ohio, chronicled in the March-April 2005 International Educator the experience of helping 11 Earlham students scale 19,340foot Mount Kilimanjaro in 2003. Penhale says that before embarking on her first Kenya trip, “I felt I could do it because Patty Lamson said, ‘Of course you can do it.’… I love the way that office runs and their attitude. They are supportive and nonbureaucratic.”

Rajaram Krishnan, an associate professor of economics who specializes in development and the environment, signed up for a faculty development trip to Japan in 2001 funded by the Freeman Foundation. He recalls going to Chuck Yates (director of the Institute for Education on Japan) and expressing doubts that he would “do anything meaningful related to Japan in my professional life.’ And Chuck said, ‘Freeman has given us this grant to open people’s minds, so come along.’” Two years later, Krishnan put the experience to use in a new course on the political economy of South and Southeast Asia, and in 2005 inaugurated Earlham’s first study abroad semester to his native India.

Krishnan also directed the Kenya program in 2002. His interest in the environment made it a good fit, but the economist also felt like he was “following a template, because the Kenya program had been around for 25 years. There were things I would have done differently.” He once had counseled his wife Subha, a special education teacher, to stop talking about things she would do differently and become a principal herself. She did so with great success. “So the advice I gave my wife, I finally gave myself: If you think you’re all that bright, why don’t you put together a program of your own? It seemed to me the natural place to do that was South Asia,” the economist said.

Krishnan wanted his program open to all students. He also realized that to operate yearly, it could not depend on the availability or specialty of a single professor. “I wanted to make sure it was an Earlham program, and not a Rajaram program,” he said. He went through the course catalog and found 40 courses that could be taught at the women’s college in Chennai that serves as the program’s base, and he “roped in three colleagues willing to come along for the ride” and lead the program in subsequent years.

Bennett, a political philosopher, said the roots of Earlham’s internationalism stretch back more than a century, when Earlham graduates ventured out as teachers and missionaries to the Middle East and Japan. “We have been receiving students from the Friends School in Ramallah since the 19th century,” said Bennett. The college also has long ties to the Friends School in Tokyo. At the end of World War II, Brigadier General Bonner Fellers, who spent two years at Earlham before transferring to West Point, was serving as senior aide to General Douglas MacArthur. The story is told by Landrum Bolling, president emeritus of Earlham, that it was a conversation with the U.S. wife of the headmaster of the Friends School that convinced Fellers—and through him, MacArthur—that the United States should treat Emperor Hirohito with respect, not as a war criminal.

Earlham was one of several Midwest colleges that enrolled Japanese-American students during World War II who otherwise would have been interned with their families in camps in the Western United States. After the war, Earlham’s Quaker leaders “looked at one another and said, ‘Somebody has to start the work of reconciliation with Japan. Why shouldn’t it be Earlham?’” said Bennett. Its Japanese Studies program was built by the late Jackson H. Bailey, an alumnus and protégé of the famed Harvard scholar Edwin O. Reischauer. Reischauer journeyed monthly to Richmond to give a faculty seminar while Earlham set up its Asian studies program in the 1950s with support from the Ford Foundation. Earlham developed an exchange that still flourishes with Waseda University, a prestigious private institution in Tokyo.

Bolling, president from 1957 to 1973, remembers a conversation with Reischauer about whether Earlham could offer Japanese studies without teaching the language. “He said, ‘If you’re serious about this program, you have to teach the language. Just do it.’” Reischauer, who later served as ambassador to Japan during the Kennedy administration, confessed an ulterior motive: his Harvard program was losing half its graduate students because they could not master Japanese. It would be better for Harvard—and for East Asian scholarship—if Earlham helped promising students get a head start on the language. Earlham today offers nearly two dozen courses in its Japanese Studies major, and 15 more in its Japanese Language and Linguistics minor. It also runs student exchanges between Waseda and the 26 campuses belonging to the Great Lakes Colleges Association (GLCA) and the Associated Colleges of the Midwest (ACM).

Bolling, the 93-year-old president emeritus and director at large for Mercy Corps, the international humanitarian agency, has been deeply involved in the search for peace in the Middle East for decades. During the Carter administration, he served as a back channel of communications with the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and Yasser Arafat years before the United States recognized the PLO.

The Organic Growth of Earlham’s International Side

“A lot of things have grown here not by plan, but by kind of organic logic,” said Bennett, a Quaker. “The same spirit of exploration and commitment that led us into Japan has led us into lots of other places; not everywhere. But the organic quality of the growth of our international commitment means it’s deeper and sturdier than it might have been if it had been top down in response to some grand plan.” As an example of Earlham’s “organic” growth, consider how its international enrollments grew from 3 percent in 1997 to 10 percent by 2004. It did not happen by chance, but it did not happen by decree, either.

Under the leadership of Jeff Rickey, the dean of admissions and financial aid, the admissions office began actively recruiting more international students. Senior Associate Dean Musa Khalidi was given a budget to travel around the world and entrusted to award as many halftuition scholarships as he saw fit to deserving international students, in addition to two full scholarships.

“Ninety-eight percent of the international students receive financial aid,” said Khalidi, who graduated from Bethlehem University in the West Bank before earning a master’s degree from the University of Notre Dame. He laughed when asked if applicants are surprised to find a Palestinian Muslim in a senior admissions post at a Quaker college in Indiana.

“It really does not come as a shock to many people. With the way Quakers approach their day-to-day life and education, it’s a very, very normal and natural thing,” he said. “Students and families sometimes find it exciting to hear a different accent and find a different cultural and religious background in Richmond, Indiana.”

Khalidi met his future wife, Kelley LawsonKhalidi, the associate director of Earlham’s international programs office, when the Earlham alumna was leading the Jerusalem program in 1991 and he was teaching her students. She speaks Arabic, French, and Spanish, advises international students, and works closely with international faculty.

Both believe that personal attention is one reason international students are drawn to Earlham in growing numbers. “Some schools think it’s a matter of creating a financial aid policy, and when you implement that, you are going to find (more) international students coming to your institution. It’s really not that easy,” said Khalidi. “Kelley and I are on the phone on a daily basis talking about international students. International families appreciate knowing that there is a person they can call and say, ‘Can you tell me what’s happening with my daughter? I can tell she is homesick; she’s not happy.’

“And when they hear that Kelley has already met with their daughter, they really love that,” he said. “It pays off because if a family is happy, they are going to spread the word. …When they send their son or daughter to a place like Earlham, they don’t have many worries.”

Khalidi, director of international student admissions, makes a half-dozen recruiting trips a year. When he made a presentation on international students at a faculty retreat in August 2005, he received an ovation. “The clapping and the joy and the happiness would energize anybody” to recruit even harder, he said.

Khalidi has recruited several students from the global network of United World Colleges (UWC). They receive $10,000 scholarships from philanthropist Shelby Davis to attend Earlham. The 10 UWC campuses—two-year residential schools offering the International Baccalaureate (IB) curriculum—annually attract hundreds of outstanding students with demonstrated leadership skills from dozens of countries. One of the most impressive of the Davis Scholars is Jawad Sepehri Joya, who overcame polio, poverty, and the repressive Taliban regime to make a new life for himself in his native Kabul, Afghanistan.

Joya, 21, a sociology and anthropology major, was taken under wing by an Italian physician when Joya’s family brought him to a Red Cross rehabilitation facility in Kabul seeking a replacement for a broken wheelchair. The doctor recognized a spark in the boy and arranged for tutoring. Joya mastered not only languages but computer skills, and the Red Cross soon hired the 13-year-old to help with interpretation and to keep its computers running. He wound up at the United World College in Trieste, Italy, before choosing Earlham over several scholarship offers.

The charismatic Joya these days bounds around campus in a motorized wheelchair. He has represented Earlham at the annual Japan-America Student Conference. Two U.S. senators offered him internships last summer, although his first trip home to Afghanistan in nearly four years forced Joya to postpone taking up that opportunity. Joya does see a stint in Washington, DC, in his future and proudly calls himself “the model of a global citizen.”

Earlham attracts more than the usual share of students determined to save the world. Many wind up pursuing service-oriented careers. John Howell, a Harvard-educated professor of physics, said, “I remember going to my 25th reunion [at Harvard] and hearing former classmates talk about the money they made in their law firm and how successful they were in whatever. Two weeks later there was an Earlham reunion and I was hearing students talk about the work they’d done in improving agriculture in Mali and Teach for America. It was such a different orientation of what constitutes success.”

‘The Ethos of Quakerism’

Loren Pope, author of Colleges That Change Lives: Forty Schools You Should Know About, once wrote about Earlham: “If every college and university sharpened young minds and consciences as effectively as Earlham does, this country would approach Utopia.”

Robert Johnstone, a professor of political science, said Earlham’s Quakerism differs from other colleges’ religious affiliations. “This is not a Baptist school in the sense that Baylor University is, it’s not an Ohio Wesleyan. But the ethos of Quakerism pervades the place, the emphasis on social justice, on conflict resolution, on simplicity. In so many ways, the spirit of Quakerism abides here and always has” even though most of the faculty are not Quakers, said Johnstone.

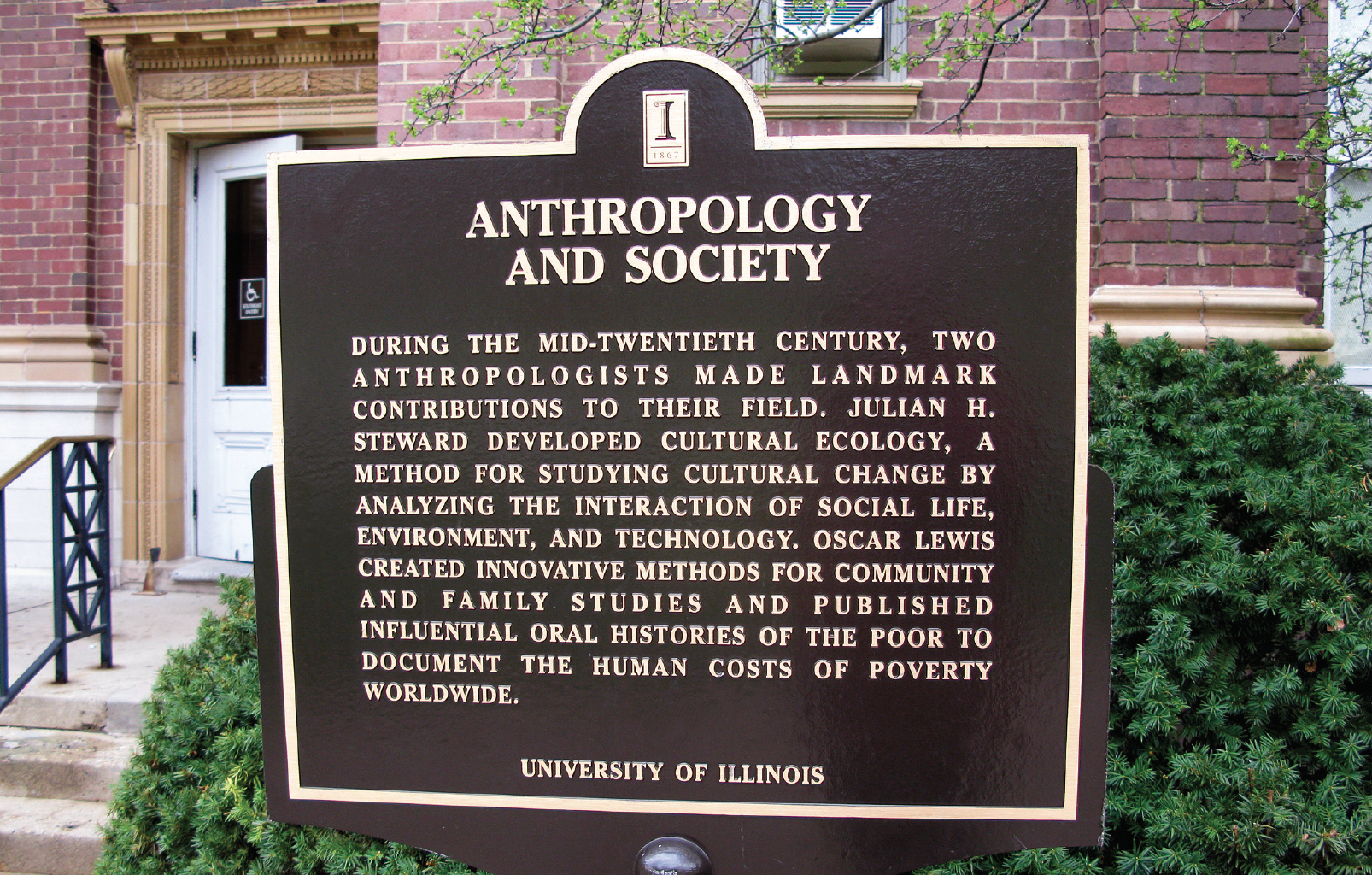

Earlham offers a major in Peace and Global Studies and a minor in Quaker studies. The chair of Peace and Global Studies, Caroline Higgins, recently found herself on conservative academic gadfly David Horowitz’s list of “the 101 most dangerous academics in America,” along with Noam Chomsky, Derrick Bell, Angela Davis, Bernardine Dohrn, and others. Horowitz told the Palladium-Item, Richmond’s newspaper, that Earlham needs a professor of military science to balance what students are taught in Higgins’ classes.

The Quaker school has no professor of military science, of course. Higgins is a diminutive 66year-old who led students to Argentina in May 2006 to visit factories occupied and run by workers and to spend three weeks in Rosario, described in a class flyer as “a city characterized by radical participatory democracy and civic education.” InsideHigherEd.com, an online daily, featured Higgins in a story about Horowitz’s book. She told Scott Jaschik, the editor, that there were only a small number of campuses where pacifist views like hers are tolerated. “If I’m dangerous, it’s because education is dangerous,” she added.

In an interview in her office, dominated by a flaming orange-and-red mural of mythological scenes painted by a Mexican artist during a year at Earlham as a Fulbright scholar, Higgins said that in her classes, “We talk not only about conflict but solutions. We look for places where things are going well, and we try to hold up examples of where peace works and violence doesn’t.”

One of her colleagues, Plowshare Professor of Peace Saoud El Mawla, got stuck in his homeland of Lebanon when war erupted in July 2006 between Hezbollah militants and Israel. El Mawla, who encountered prolonged difficulties securing a U.S. visa when Earlham hired him three years ago, had gone home to Beirut to visit family and renew his visa.

The Islamic civilization scholar told InsideHigherEd’s Jaschik in an interview by email, “This is my first war as a peace studies professor, but not as an activist and militant for peace and justice. … The war brings us to real life and puts us before the human sufferings, hopes and tears. We have to stay firm in our convictions, to spread hope, to build networks of solidarity and action trying to stop the war and to make peace. It is very, very hard but we cannot do anything else.”

Aletha Stahl, associate professor of French and Francophone Studies, helped establish a semester-long program in Martinique andhas led students to Haiti several times on May terms. She led 18 students to France in fall 2005 on a program that starts with language classes in Nantes, the port city in Brittany, then moves to the Pyrenees where students spend two weeks living and working with artisans before finishing the semester in Paris. Stahl said Earlham typically graduates three to five French majors a year.

A growing number of students are majoring in Comparative Languages and Linguistics. “We’re all finding that it’s harder even to remember who are ‘our’ majors,” said Kathleen Taylor, professor of Spanish and Hispanic Studies. “With all kinds of students interested (in languages) across majors, we don’t necessarily call them ours anymore.”

Taylor has led students to Curaçao twice, taught Papiamento during the regular term, and is preparing an online textbook of the language. When she started learning Papiamento herself, “I had no idea I would have any use for it. It’s turned out to have a lot more than I expected. The first time I taught it I had 16 in the class, and nine went with me to Curaçao on the May term. Last year I had 26 in the class and 13 went on the May term.”

“One of the things that keeps us alive intellectually is that we keep opening new doors and exploring new things,” said Taylor, who has led Earlham’s semester program to central Mexico five times. “We are expert learners and that’s a good model for our students.” Welling Hall, professor of politics and international studies, said international students are drawn in large numbers to her international studies classes. Earlham offers scholarships to students from Seeds of Peace, a camp in Maine for teens from conflicted regions of the world, including the Middle East, the Balkans and Cyprus, and Earlham students often work there as counselors.

Hall advises the Model United Nations Club, which hosts a major competition each spring for high school students from across Indiana. Hall was skeptical when two international students approached her a few years back with the idea of having the high schoolers deal with a scenario in which a meteor had wiped out much of North America, with survivors’ forced to seek refuge in the southern hemisphere. They recruited an Earlham physics professor to lecture on meteor strikes, and the science fiction scenario for a futuristic U.N. was a big success.

Applications to Earlham have climbed, but increased selectivity carries a price. Clark, the provost, said, “Increasingly we’re having to turn away students that we are pretty sure would succeed and flourish there. We are still thinking through how to adjust to that.”

Bennett notes with pride that one-fifth of Earlham students qualify for federal Pell Grants (the average family income for those need-based awards is $15,000). “We’re a higher-need student body than most of our competitors. We love that. The value added we do for the world is huge,” said Bennett.