Communications

NAFSA Resources for Operational Resilience

When a Reporter Calls

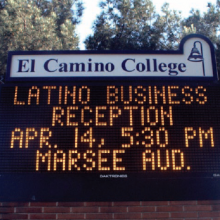

2005 Spotlight El Camino College

In the state that fired the first shot in the property tax revolt with Proposition 13 more than a quarter- century ago, what are the odds that voters in the South Bay of Los Angeles would approve a $394 million bond issue for their community college?

The odds might be long, but by a margin of 62–38, some 110,000 voters in this ethnically and economically diverse area of southern California did just that in November 2002 by passing “Measure E,” a capital improvement bond, for El Camino College. El Camino is an ambitious institution serving nine cities: El Segundo, Manhattan Beach, Hermosa Beach, Redondo Beach, Torrance, Lawndale, Hawthorne, Lennox, and Inglewood. It opened its doors in 1947 as El Camino Junior College, with 450 students attending classes in nine renovated barracks from Santa Ana Army Air Base. Today 25,000 students are enrolled on the campus, which offers 2,500 classes in 85 programs and boasts a 12,500-seat football stadium.

Painstaking Pursuit of Grant Funding

El Camino is also a standout in international education, enrolling nearly 700 students from other countries and sending more than 100 each summer to study in England, France, China, and New Zealand. Thanks to an aggressive pursuit of federal grants and exchange opportunities and a spirit of inquisitiveness among its faculty, El Camino College in the past five years has gotten involved in exchanges that took its faculty to Ukraine, Poland, Italy, and Lebanon. It was one of two community colleges chosen to participate in the State Department–sponsored Global Experience Through Technology (GETT) initiative that links classrooms in Europe and the Middle East with campuses in the United States.

“There was a time probably when some folks here thought, ‘Well, why are we doing this? We have the general education curriculum to address,’” said Gloria E. Miranda, the dean of Behavioral and Social Sciences and a historian on family life in Spanish and Mexican California. “But with the world today, and with the tragic series of events in the last several years, we really need to understand the multicultural world we live in. And since much of the world migrates to the United States, we must understand the people who come to this country, as well.”

Bozena (Bo) Morton, acting director of the Center for International Education and a prolific grant writer, said, “With international grants, we’ve been extremely lucky. We got almost everything we applied for with one exception.” The Polish-born Morton immigrated to the United States after a decade living in then-Czechoslovakia and teaching English at University of Silesia in Cieszyn, just over the border in Poland.

The lives and careers of several El Camino faculty have taken remarkable international turns thanks to Morton’s uncanny grantswomanship, none more so than that of Antoinette Phillips, a professor of childhood education.

Alumna Leads Child Development Programs Abroad

Phillips is an El Camino success story. She earned her associate’s degree in 1976, then joined the faculty after completing a master’s degree in childhood education. “I was one of those late bloomers. I didn’t go to college until my children started school. I lived right down the street and rode my bike so I didn’t have to worry about parking,” she said. She excelled in the classroom, but was astonished one day when a mentor told her, “You know, you could do this. You could be a professor.”

Phillips volunteered to go to Ukraine for three months in 2001 to teach child development and American instructional techniques to Ukrainian professors and their students. El Camino had secured an $180,000 three-year grant under a State Department program that links U.S. colleges with universities in the newly independent states of East Europe. El Camino’s partner was Dniepropetrovsk National University (DNU) in Dniepropetrovsk, a city of 1 million people on the Dniepro River that was closed for military research during the Soviet era.

“At a faculty meeting Bo asked, ‘Who would like to go to Ukraine?’ and I raised my hand. That’s how it all started,” said Phillips.

While their project partners in DNU’s Educational Psychology Department spoke fluent English, most of the students and many of the professors with whom Phillips interacted in other places did not. She relied on students and the project’s co-director, Tatyana Vvedenska, to translate for her. Vvedenska, a dynamic English professor at DNU, wound up teaching ESL classes at El Camino on a faculty exchange in Spring 2004.

The polyglot Morton calls Phillips “the bravest person” for taking on the assignment. Her dean, Gloria Miranda, accompanied Phillips to Ukraine, but she returned shortly afterwards. “I was there by my lonesome for three months until Bo came over for the last two weeks,” said Phillips. In dozens of classrooms and academies, she demonstrated how classes could be taught in more creative ways than relying solely on lectures.

“I had to have an interpreter all the time. That was a little uncomfortable, because it takes away some of my spontaneity—I had to wait after each sentence for it to be translated—but we managed,” she said. “I visited a lot of schools from preschool up to universities, went to academies, and spoke to a lot of different classes about the American way of life and American education.”

She’d return to her apartment after a day of classes, and using a dial-up connection, teach two education classes online to her students back in California, sharing with them glimpses of life in Ukraine’s third largest city.

Apart from one trip to England, Phillips had not previously traveled outside North America. “It was such a transforming experience for her. What I find so fascinating is that you have faculty who really have never seen the world,” said Miranda. “Even though they are experts in a discipline—Antoinette is one of our distinguished faculty awardees—they have not tested how their teaching techniques would apply in a global setting.”

Phillips enjoyed the experience so much that she volunteered to do it again two years later when Morton landed a grant from the Fulbright Educational Partnership Program allowing El Camino to partner on teacher training with the Cieszyn branch of the University of Silesia in Poland, where Morton once taught. There Phillips found the classrooms filled with eager future teachers who spoke English fluently.

Expanding Teacher Exchanges, Online Offerings, and Telecourses

El Camino sent six faculty and administrators to DNU over four years, and an equal number from the Ukrainian university journeyed to California to visit El Camino’s landscaped campus a few miles south of Los Angeles International Airport. Most of these exchanges lasted two to three weeks. Phillips made a return visit in April 2003 with Elizabeth Shadish, an El Camino philosophy professor who is a skilled hand at distance education.

At home, El Camino’s distance education courses—both online via computer and through telecourses provided on videos—are especially popular with students who cannot fit regular class hours into their work or family schedule. “They may be working 40 hours a week or they’ve just had a baby or they have two or three children at home,” said Phillips.

In the Ukraine, the university students were traditional age—18 to 21—and technilogically savvy. However, most faculty were lacking in technological literacy, said Shadish, who earned her Ph.D. at Purdue University and taught at California State University at Northridge before joining the El Camino faculty a dozen years ago.

Like Phillips, Gloria Miranda is also a product of one of California’s many two-year colleges, Compton College. She earned her bachelor’s at Cal State University, Dominguez Hills, and her Ph.D. at the University of Southern California. She chaired the American Cultures and Chicano Studies programs at Los Angeles Valley College before taking the dean’s post at El Camino.

“The fact that Bo came with her unique background has really helped us and our faculty focus on what we can do to expose ourselves and our students to the world around us,” Miranda said.

“The faculty in my division who’ve participated have been almost re-energized by these opportunities.”

With the Ukrainian project, Morton said, “We found out that sending the same faculty members more than once is really a good practice. They are able to do so much more during their second visit because they don’t have this adjustment period.”

The success of the Ukrainian exchange convinced El Camino President Thomas M. Fallo to tap some of El Camino’s own resources to support the partnership with the University of Silesia in Cieszyn, Poland. It is a city and region with a turbulent and colorful past and a multicultural mix of identities and ethnicities.

In Poland, Phillips found teacher educators intrigued by her teaching methods, but loathe to give up their reliance on rote lectures. The Polish educators were struggling with how to meet a new mandate for more kindergarten teachers.

GETTing More Opportunities

For it’s next international venture, El Camini was selected to participate in the State Department’s International World Cultures Project using the Global Experience Through Technology (GETT) model pioneered by East Carolina University. Recognizing that fewer than 2 percent of U.S. college students study abroad, this project is designed to expose students to new cultures through virtual classrooms shared with university students in other parts of the world.

This opportunity almost fell into El Camino’s lap.

“After Ukraine we got a good reputation. That project worked well and accomplished what it was supposed to accomplish,” said Morton. “One day I was sitting in my office and I got a call from a new person at the Department of State who told me she was putting together a virtual classroom project. She had heard about the distance education component to our work.”

El Camino partnered again with DNU in this new project, but it also needed to find two other institutions to work with, including one in the Arab world. “Sometimes it’s not easy to put a partnership together. Sometimes you just have to dig, you have to cold call,” said Morton. “I sent cold e-mails. That’s how I came up with the Italian partner. Somebody on our faculty said the University of Modena at Reggio Emilia was the best in Italy on early childhood education, and I thought, ‘If we are going to connect with somebody, why not the best?’”

El Camino sent Elizabeth Shadish, the professor of philosophy, and Joanna Medawar Nachef, a music professor and choir director, to Europe with bags bulging with videoconference equipment bound for three partner institutions: DNU in Ukraine, the University of Modena at Reggio Emilia, and the Lebanese University in Beirut, Lebanon. Nachef is an accomplished conductor and choir master who was born in Beirut but earned her degrees (including a doctorate from USC) in the United States. She speaks Arabic and still has extensive contacts in the Lebanese capital.

The two El Camino teachers set up a pilot world cultures course in which a single class of students from the four institutions rotated working with each other online for three to four weeks at a time.

“We had to create a schedule that involved coordinating across time lines, semesters starting at different times, and vacations and holidays happening at different times. You just put together a grid and get a schedule down so that nobody has off times, or at least not too many off times,” said Shadish. “At any point, two institutions were working with each other, ideally for three or four weeks. While we’re talking with Italy, Lebanon is talking with Ukraine. Next rotation we’re talking with Ukraine, while Italy and Lebanon are talking.”

For the pilot, Shadish and Nachef selected El Camino honors students from their own classes. They received no credit, “but they were there the whole semester at 8 in the morning. They saw the value in this,” said Shadish.

They had no trouble finding volunteers, agreed Nachef. “Even [at times] when there is no picture and they are only hearing them on the other end, the electricity in the room is fascinating,” she said. “These students went back to the choirs and my other classes, saying, ‘You can’t believe how exciting it is.’” Students were often disappointed when the allotted hour ran out. “They don’t want to leave the room. They look at their watches. We say we have to end the session and they say, ‘We don’t want to,’” Nachef said.

Nachef laughed as she recalled one incident of strained communication. One student asked a young man in Lebanon if they had rites of passage for special birthdays. She had in mind La Quinceañera, the Latin celebration for a girl’s fifteenth birthday.

The Lebanese student took umbrage, typing back, “Do you think we are barbarians? We dance around fires?”

The panicked American called out for help to her professor, saying, “Dr. Nachef, I don’t know what to say. He thinks we’re putting them down.”

Amity prevailed after the cultural reference was explained.

Shadish and Nachef plan to offer the cultural exchange course again and involve new countries and universities in GETT. “Where this program can go is so exciting,” Shadish said. “[GETT] is such a pioneer experience that nothing you do is wrong. We’re creating the standards. We’re very free to explore what works.”

The Possibilities Seem Endless

El Camino also won Fulbright-Hayes funding from the U.S. Department of Education to send 15 teachers—Spanish language teachers and teacher educators from its own faculty and teachers from local elementary schools—on a four-week language and cultural study trip to Guadalajara and Oaxaca, Mexico.

Miranda said El Camino is developing a proposal to partner on an early childhood initiative with two other community colleges in different parts of the United States and three universities overseas.

The possibilities seem endless. “I have a part-time teacher whose father is retired from the University of Ghana,” said Miranda. “And Bo and I have been talking about a grant that includes China. We’re in such a key position here on the Pacific Coast, and we want to infuse our curriculum with more content that pertains to the Asian world.” El Camino has already won backing from the Council for International Exchange of Scholars for its request to have a Middle East scholar spend a semester at the campus as a Fulbright Scholar-in-Residence.

The faculty and the administrators keep coming up with ideas and Bo Morton, as Miranda put it, “keeps hitting home runs for us.”

Even before getting a $394 million makeover courtesy of Measure E—it will take years to complete all the new projects and improvements—El Camino has established itself as a college on the move.

El Camino College

2013 Comprehensive University of South Florida

When the University of South Florida reorganized its international programs, it squeezed into two words the name of the wide-ranging operation: USF World. Karen Holbrook, senior vice president for global affairs and international research, describes USF World as “a mindset, a culture, a strategy, and a reality” as well as the particular branches of its international operations nestled in the Patel Center for Global Solutions. Holbrook, a biologist and former president of Ohio State University, answered a call from USF President Judy Genshaft to come to Tampa in 2008 for a short period to watch over its burgeoning research enterprise. Five years later she’s still there, arriving in her sports car at the Patel Center at dawn and staying late. “It’s really fun, probably more fun than anything I’ve ever done,” said Holbrook. “I’ve really, really enjoyed being at USF World.” Her idea of fun includes spending hours on a cruise designing an intricate schemata for USF’s quest to become a global research university, with circles within circles and boxes crammed with goals, metrics, and strategies. A vision plan she drafted is 380 pages and a PowerPoint presentation to the Faculty Senate contained 120 slides. “I go through them fast,” she said.

USF is going fast. Built on a World War II practice bombing range and opened in 1960, what was largely a commuter college now is a system institution with 48,000 students and $411 million in research grants and contracts. All freshmen must live on the green campus lined with graceful live oak trees. It has weathered $125 million in state budget cuts. The out-of-state tuition of $16,260 (Floridians pay $6,330) is a draw for the 2,368 international students, and more are coming through a new partnership with INTO University Partnerships, the British recruiting enterprise that places students from China and elsewhere into intensive English and academic pathway programs at allied universities (Colorado State University, another Simon Award winner, is another INTO school). On a campus where Floridians once comprised 96 percent of students, USF aims to double international enrollments to 10 percent by 2018. “We’re doing it to enhance the quality and moreover the relevance of the educational experience,” said Provost Ralph Wilcox. “We believe we’ve got something to offer international students, but they also have an incredible amount to bring to us.”

Serving the Needs of a Global Community

Genshaft, president since 2000, is carrying out her third strategic plan, each more globally focused than the preceding one. That is only natural for Tampa Bay, she said, home to 480 multinational corporations as well as Florida’s busiest port and MacDill U.S. Air Force Base, headquarters for U.S. Central Command (CentCom) and Strategic Operations Command. Genshaft said one business leader told her pointblank that his company cannot alone teach employees “tolerance, cultural knowledge, and the value of international activities. You’ve got to do it and then they’re better employees for us.” The military, too, relies on USF’s help to bring academic perspectives to grappling with the world’s trouble spots and resolving problems peacefully instead of using “kinetics,” as retired three-star Marine Lt. General Martin Steele, associate vice president for veterans research and executive director of USF Military Partnerships, delicately put it.

Learning Mandarin in Tampa Bay and Qingdao

USF secured a Confucius Institute in 2008 by promising to recruit its first tenure-track professor of Mandarin. Eric Shepherd got the job. “It was unfathomable to me that at that time we had 40,000 students and basically no Chinese language program beyond an introductory class taught mostly in English,” he said. Now the Department of World Languages offers a Chinese minor, and 200 students attend classes taught by three professors and three instructors. “We came along a little later, but we’re quick learners,” said Genshaft.

Shepherd, a master of the Chinese storytelling performance art called Shandung “fast tales,” sends students to Qingdao University and Ocean University of China for up to 18 months of classes and internships. “They learn how to work at a professional level,” he said. “If they’re an international business major, they learn to do international business in Chinese. If they’re a chemistry major, they’re learning how to do chemistry in Chinese.”

As an undergraduate Victor Florez, 23, now working for the Confucius Institute, finished fourth in a monthlong, nationally televised “Chinese Bridge” language contest for international students. Florez, a Miami native of Colombian ancestry, came to college with a strong desire “to learn a language that was completely alien to me.” Mandarin fit the bill. “My first year I studied three hours a day,” said Florez. “If you put in the work, it’s inevitable that you’ll come out speaking fluent Chinese.”

Ambassadors for Education Abroad and a Gateway in the Student Center

Some 2.5 percent of USF students graduate with an international experience. Some 844 earned credit abroad in 2011–2012. Holbrook wants to grow that number exponentially. Genshaft and her husband donated more than $1 million to endow Passport Scholarships of $2,500 to $5,000. USF World recruits returning undergraduates to serve as “GloBull Ambassadors” for education abroad (the Bull is the university mascot), and the professional staff has grown from 5 to 11. Since the Patel Center sits at a distance from the heart of campus, USF World opened a satellite study abroad office in Marshall Student Center. “We needed to be more central to be able to catch and serve the students. We call it the Gateway Office,” said Amanda Maurer, director of education abroad. Maurer underscored the importance of the GloBull Ambassadors in convincing fellow students to pursue education abroad. “We can say it ourselves five or six times, but if a student goes up there and says, ‘You’ve really got to do this; it changed my life,’ they listen,” she said.

A new Global Citizenship program rewards up to 200 freshmen and sophomores who study global issues with $2,000 scholarships for education abroad. Anthropologist Karla Davis-Salazar, who has excavated Mayan ruins in Honduras, led the first cohort to Panama in 2013. Despite tight budgets, the provost found $400,000 to fund the Global Citizenship initiative. “Part of my goal for the future is (finding out) why more students aren’t interested. What do we need to do to open their minds?” said DavisSalazar, now an associate dean.

The international services staff also has expanded from six to nine. The INTO partnership will bring more Asian students to Tampa. USF also draws students from Latin America, including 60 undergraduates from Venezuela. Among them are engineering students Ana and Juan Lopez Marcano, siblings who said the courses and workload are harder back home but the research opportunities much greater at USF. Ana, 19, who was president of her high school class, hopes to design biomedical devices. “I really like it here,” said her 20-year-old brother, aspires to land a job at a tech giant such as Microsoft and learn “the cool stuff.”

Establishing the USF Brand in Far Places

Roger Brindley, associate vice president for global academic programs, sees his job as “brand profile development writ large.” He works on expanding international partnerships. “For the life of me I can’t understand why people in India have heard of Harvard, but not South Florida,” quipped Brindley, a British-born expert on early childhood education. USF World now has two people in Delhi who work on recruiting students as well as finding new research opportunities and promoting economic development. USF has more than 40 faculty members of Indian heritage and 240 students from India.

“For the life of me I can’t understand why people in India have heard of Harvard, but not South Florida.”

The university provides grants up to $12,000 to faculty to generate research, scholarship, and “creative activity” with counterparts at five partner universities in Ghana, China, and the United Kingdom. Its Ghana Scholars Program, which brings faculty from the University of Ghana and the University of Cape Coast to USF to complete dissertation work, recently received an honorable mention Andrew Heiskell award from the Institute of International Education.

These partnerships are vital to USF’s achieving its goal of becoming globally engaged, said Brindley. No one “thinks becoming globalized is switching on a light. A generation from now the only relevant universities, in our opinion, will be globally engaged. We have a responsibility to do that work and be one of the universities that succeeds.”

Faculty Interests Drive Internationalization

Michael Churton has witnessed the changes as a longtime professor of special education with a deep international bent. An authority on distance learning, he was a Peace Corps volunteer in Malaysia in the 1970s. To honor the memory of a friend killed in Vietnam, he flew to wartime Saigon and applied for a teaching job just before the government fell. He has made Southeast Asia a focus of his career, studying disabilities among indigenous people in Borneo as a Fulbright Scholar, coordinating a USF partnership with the University of Malaysia-Sarawak, and working with Vietnam’s education ministry on e-learning courses for medical students. He is an honorary professor at Hanoi Medical University and has travelled to Vietnam a dozen times and to Malaysia 20 times.

When he joined the USF faculty in 1994, “there was no support from any place” for such work overseas, he said. “It was faculty members on their own. Slowly, as a new administration and new people came in, the evolution began and now we’re much farther along.”

“USF World has greatly enriched the possibilities for faculty and students. I can’t tell you how much they have helped us to stretch ourselves,” said education psychologist Darlene DeMarie, who established a model child care center at the University of Limpopo on a Fulbright in South Africa.

More than 120 Peace Corps volunteers have earned master’s degrees under the tutelage of James Mihelcic, a civil and environmental engineering professor, first at Michigan Tech and since 2008 at USF. Mihelcic, a prolific researcher, was recruited to be a 21st Century World Class Scholar, a distinction created by the Florida legislature. He finds low-tech solutions to water and sanitation problems in developing countries and heads a multi-university consortium that recently won a $3.9 million National Science Foundation grant to recover energy, water, and nutrients from wastewater.

Mihelcic said the Peace Corps volunteers in his master’s program are equipped to tackle complex sanitation problems. “It’s a scarce skill set,” said Mihelcic. “The Peace Corps has had trouble attracting and retaining engineers overseas.” Cohorts of 20 students spend two semesters at USF studying not just environmental engineering, but anthropology and global health. “Part of our job is to get students to understand you can do a lot of behavioral change besides the technological solutions,” he said.

Still Building “Who We Are”

In separate conversations, administrators and faculty alike describe USF in terms that suggest a large canvas still being painted. As Davis-Salazar, the anthropologist, put it, “We are still building who we are.” It is a collegial undertaking. At the helm of USF World, Holbrook has displayed a prodigious capacity for organizing and putting forward her own ideas, but she said they are “only the starting point. What’s exciting is other people’s ideas.” More than 100 faculty are involved in workgroups fleshing out USF’s international vision plan and coming up with metrics to gauge the university’s progress. “We want people to know about it and be excited about it,” Holbrook said. “When you do it by yourself, it’s just out there for everybody to attack, and that’s what I hope everybody will do.”

“There’s no doubt that the needs of international students are on the minds of most people at the university.”

The words have been backed up with dollars and actions. Wilcox, the provost, said, “We have invested and created a budget for USF World in difficult times.” Even with a 25 percent, $104 million cut in state appropriations over the past four years, “we had the focus, the discipline, and the strategic appetite to say the world is important and USF World is important.”

“This is a high-energy university,” said Wilcox. “This is an incredibly ambitious set of goals….We all realize that being a 50-something-year-old institution if we aspire to the level of achievement we do, we’re going to have work harder than other, older institutions because they want to improve and get better, too. We’re not going to sit still. There’s so much more to do.”

2014 Comprehensive Rutgers The University of New Jersey

The recent move by Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, to the Big Ten Athletic Conference might seem far afield from its ambitions to expand its international connections and stature. But even before playing Penn State and Michigan on the gridiron, Rutgers became a full-fledged member of the Committee on Institutional Cooperation (CIC), the vehicle that brings presidents from the Big Ten and the University of Chicago together on academic pursuits. As President Robert Barchi told a Star-Ledger reporter after his 2012 installation, “We’re playing with the big boys now.” Two years in advance of the 250th anniversary of its founding as the eighth college in colonial America, Rutgers is undergoing a metamorphosis with the purpose of living up to the slogan emblazoned on its ubiquitous red bus fleet, “Jersey Roots, Global Reach.”

Rutgers looms large in what Executive Vice President of Academic Affairs Richard Edwards called “the thoroughly globalized landscape that is New Jersey,” with 65,000 students on three major campuses in New Brunswick and Piscataway, Newark, and Camden. With the 2013 merger of New Jersey’s two medical colleges and six other health schools, its budget skyrocketed in a single year from $2.2 billion to $3.6 billion and the university is undergoing a building boom. Rutgers University-Newark, with more than 12,000 students, bears the distinction of being the nation’s most ethnically diverse university, according to U.S. News and World Report, and the main campus along the Raritan River is not far behind. Rutgers serves a densely populated state with the dubious distinction of having less capacity at public universities and exporting more students than any other. Only 8 percent of Rutgers undergraduates come from out of state, and until recently the university actually was faced with the loss of state aid if it enrolled more outsiders.

New Jersey Governor Chris Christie and the state legislature scrapped that penalty. Rutgers today enrolls nearly 5,900 international students; their ranks swelled by 1,000 with the medical and health school merger. A big push to attract undergraduates from China and elsewhere boosted their numbers by 60 percent in two years. Now, like other campuses that have gone this route, Rutgers is figuring out how best to ensure their success at this widely dispersed, decentralized institution.

“We’re constantly thinking about how to bring different groups together and think in different ways. That’s where the most exciting moments happen. That’s where the knowledge is. That’s what internationalization is all about.”

Internationalization Not a Stand-Alone Goal

Barchi, a neuroscientist, moved swiftly after his 2012 installation as Rutgers’ twentieth president to produce a new strategic plan, the university’s first in nearly two decades. Adopted in February 2014 after 18 months of brainstorming and soul-searching, the strategic plan offered a blunt assessment of Rutgers’ weaknesses in comparison with the nation’s top public research universities and laid out four priorities for “achieving greatness”: envisioning the university of tomorrow, including wider use of technology in teaching; building a world-class faculty; transforming the student experience; and enhancing Rutgers’ public prominence. While there are international ramifications to all these themes and priorities, internationalization was not singled out and that was intentional, Barchi said.

“The way we’re looking at it going forward is that globalization is something we’re doing in all of our programs. It’s not a mission or a goal in and of itself that we are going to emphasize at the expense of other academic priorities,” said Barchi, former president of Thomas Jefferson University and provost of the University of Pennsylvania. One of his first moves was to scuttle his predecessor’s plans to open a 5,000-student satellite campus in Hainan, China, with South China University of Technology.

Nonetheless, the trajectory of international programs is upward, especially since the 2011 creation of the Centers for Global Advancement and International Affairs (GAIA), which unified activities across Rutgers’ schools and campuses. The vision came from Joanna Regulska, vice president for international and global affairs and a professor of women’s and gender studies and geography who has been honored by her native Poland for contributions to democracy and civil society there. She started with a staff of 20. Three years later more than twice that many are at work in GAIA’s three frame buildings on the College Avenue campus and outposts in Newark and Camden. Fueling the growth was GAIA’s 2 percentage point share of a new, 4.5 percent first-year tuition fee.

Regulska previously had directed international programs for the School of Arts and Sciences alone. “I pushed for GAIA for a very long time. Things were moving even before I had an official portfolio,” she recalled. GAIA selects a biennial theme and sponsors scores of international events each year, including nearly 100 on global health in 2013–2014 alone. “I’m the bridge builder,” said Regulska. “We’re constantly thinking about how to bring different groups together and think in different ways. That’s where the most exciting moments happen. That’s where the knowledge is. That’s what internationalization is all about.”

Seeding Public Health Degrees and Service Learning in Brazil

GAIA also had more than $240,000 at its disposal in 2012–2013 for seed grants to faculty to spur international collaborations and internationalize curricula. In an institution that expends more than $700 million in research, a few thousand dollars from GAIA isn’t much, but faculty are using the grants to reel in larger support.

Stephan Schwander, a professor in the School of Public Health who studies how pollution weakens resistance to tuberculosis, secured $10,000 from GAIA and $5,000 from his department to launch a global health concentration within the public health master’s program. “It’s a start and a recognition from Rutgers that this educational activity is needed,” said Schwander, who leads an interdisciplinary global health working group. Studying TB in the lab “has shown me very clearly that biomedical work alone is not the solution,” said Schwander. “Tuberculosis is a disease of poverty” and working across disciplines will “come closest to understanding what’s going on.” Rutgers recently got its first Fulbright Visiting Scholar in Global Health. Susan Norris, a professor of nursing who conducts research in favelas and twice has taken students to Brazil for service learning, also got help from GAIA. “An $8,000 grant can get me to Brazil several times,” said a grateful Norris.

Instilling a Study Abroad Culture

Fewer than 1,000 students a year study abroad, including 275 from Camden and Newark. “Given the size of the university, we still have a long way to go,” said Giorgio DiMauro, director of the Center for Global Education. “Cost is a big factor. We’re addressing that by offering programs of different lengths and types, and exploring ways to lower the cost of study abroad.” Changing the academic culture also “is an important piece. Study abroad has not been as well integrated as it could be into the academic majors,” he added.

Eugene Murphy, GAIA’s assistant vice president, concurred. “We need to rationalize the way international education opportunities are structured here. Right now, they cost too much,” said Murphy, an anthropologist and former NYU administrator who took GAIA’s number two job in 2013. “It’s a stretch for a lot of students.”

Jorge Schement, vice president for institutional diversity and inclusion, called Regulska a pioneer who “stepped forward with a vision and promoted that vision at a time when nobody cared, and then people began to see the wisdom of what she was doing. She began opening doors that brought the diversity identity together with the international identity.” The diversity identity is strong in a melting pot state where one person in five is foreign born. “Diversity is us,” said Schement.

The Care, Feeding, and Recruiting of International Students

New Brunswick is 30 miles from New York City and 50 miles from Philadelphia, which helps draw international students. But there were no formal international recruiters until three years ago when Vice President of Enrollment Management Courtney McAnuff conceived the 4.5 percent first-year tuition fee. It allowed him not only to hire a recruiter but also to add a counselor or other support person for every 150 additional international students.

An e-mail from two incoming Kenyan students asking McAnuff how they would recognize him upon their late night arrival at Kennedy International Airport made McAnuff (who drove in to get them) realize Rutgers needed to arrange vans as an alternative to $200 cab rides. Rutgers opened a 24-hour diner to give international students a place to eat over holiday breaks when the main dining halls were closed.

The Center for Global Services’ share of the fee allowed Urmi Otiv, the director, to hire new staff. That still leaves each staff member responsible for more than 800 students, but “we’re in a much better place than we were and looking to get better,” said Otiv. She counsels students, “‘Yes, Rutgers is huge and overwhelming, but the trick is to create your own small Rutgers’” by making friends and networking.

Lobbying Congress as Part of an American Education

Making friends was not a problem for Jianyu Yeyang, 21, a sophomore from Kunming, China. “I’m quite Americanized,” said the political science and finance major, who goes by the nickname Cobra and attended U.S. high schools for two years. He took part in a Rutgers study abroad program in Beijing, studying with international students as well as locals who mistook him for an American and were surprised he spoke Mandarin.

As a volunteer Global Ambassador for the Center for Global Education, he was part of a Rutgers contingent who traveled to Washington, D.C., on NAFSA’s Advocacy Day to lobby Congress for the Dream Act and other immigration changes. (Yeyang made a pitch to staff of New Jersey’s senators for making it less difficult for international students to obtain visas). Yeyang, wearing a varsity letter jacket, worries countrymen stick too much to themselves at Rutgers. “They’re still living a lifestyle like they’re in China,” he said.

Michael Marcondes de Freitas, 29, of Brasília, Brazil, had to make new friends when he began PhD studies in a rarefied mathematics field because there were few students with whom he could converse in Portuguese. “Math is so lonely, it drove me to pursue getting involved on campus,” he said.

He volunteered at international student orientations, once held in a modest-sized ballroom in the Student Center but now big enough to fill a gym, and was a leader of the Rutgers chapter of a charity, Giving What We Can, that raised funds to fight malaria. “These have been the best six years of my life,” said Marcondes de Freitas, who is off to Denmark on a postdoctoral fellowship.

Finding and Cultivating Fulbright Talent

Rutgers has dramatically increased its production of Fulbright Scholars and it’s not by happenstance. Arthur Casciato, director of the Office of Distinguished Fellowships, doesn’t wait for students to wander into his warren in historic, nineteenthcentury Bishop House; he goes out and finds them. In 2007 when the office was created, there were eight applicants and no awardees. By 2012, nearly a hundred students applied and 19 won, including Lillyan Ling and Michelle Tong.

Ling, 23, a Phi Beta Kappa English major now working for Oxford University Press, taught high school in Dobrich, Bulgaria, on the Black Sea coast. She applied at the last minute at a professor’s urging, and Casciato waived an internal Rutgers deadline that had passed. “I never say no to anyone,” he said.

Why Bulgaria? “I wasn’t interested in picking a glamorous place. At this age, I need to expose myself to as much as possible,” said Ling, the daughter of Chinese immigrants. Her choice meshed with Casciato’s advice to apply to countries with favorable selection odds. “Winning Fulbrights has a lot to do with strategy,” he said.

Tong, also Chinese-American, got an e-mail out of the blue from Casciato. “I had no idea that this sort of office really existed,” said Tong, a K-pop fan who taught in Cheongju, South Korea, and worked as a United Nations intern. “He heard about me from my French professor who was a Fulbrighter in her day.”

Building Upon Old Ties and Fostering New Connections

Rutgers is focusing on five countries to build or expand partnerships, joint research, and exchanges: China, India, Indonesia, Brazil, and Liberia. After former President Richard McCormick visited China in 2011, Rutgers established dual-degree programs with South China University of Technology, Tianjin University, and others. It also created a Rutgers China Office on the New Brunswick campus to expand ties and exchanges.

The office generates revenues for its activities by running professional development and training programs for Chinese university leaders, administrators, and others. Political scientist Jeff Wang, the director, sees a bigger purpose. “The China-U.S. relationship will be the most important in this century. There are a lot of misunderstandings between the two, so this people-to-people exchange is really the best tool to educate both sides,” said the Xian native.

A partnership with the Indian Council for Cultural Relations gained Rutgers a visiting professorship in Indian Studies. An Obama-Singh 21st Century Knowledge Initiative grant allowed it to stage a higher education leadership academy in Mumbai. U.S. Agency for International Development grants underwrite large projects in Indonesia and Liberia. Rutgers’ ties with the Universidade de São Paulo in Brazil date back 40 years.

Owing Students an Internationalized Education

Rutgers revised its tenure and promotion process in 2012 to explicitly recognize faculty members’ international activities, which Regulska said made it one of only a handful of institutions in the country to do so. She borrowed the idea from universities in Florida and Michigan. Faculty can present their accomplishments in the areas of international research, teaching, curriculum development, advising international students, grant writing, and service. Regulska said this was not only an institutional recognition of the value of international engagement, but also a recognition that it takes more time and effort to sustain such a commitment.

The tenure form now asks junior faculty to list the international courses they taught on campus or abroad and to specify the number of international students they advise. “We know it takes more time and energy to be a good adviser for international students because the student has a second language and it’s a different culture for them,” Regulska said.

Increasingly Garden State students such as Kunal Papaiya understand their own stake in Rutgers’ internationalization. The political science major believes Rutgers needs to “increase its global presence” and recruit more international students like Yeyang. “We’re not just competing with domestic students. We’re competing with international students like Cobra. We need to get more students like him in here,” said Papaiya, a senior who is eyeing a career in law and politics.

Jean-Marc Coicaud, professor of law and global affairs at Rutgers-Newark and a former United Nations official, said Rutgers must keep up not just with the Big Ten schools and other top public institutions, but elite private ones as well.

“Private universities have been in this (internationalization) business in a very, very aggressive fashion for years, giving an additional edge to students who are already very privileged,” said Coicaud. “If Rutgers misses the train, we’re allowing private universities to even deepen their advantage.”