2016 Comprehensive New York Institute of Technology

With seven campuses in four countries, New York Institute of Technology (NYIT) gives “global” an entirely new meaning. In addition to its presence around the world, NYIT boasts an exceptionally diverse student body, with nearly 20 percent of its students coming from more than 100 countries. The global perspective, as President Edward Guiliano is fond of saying, is infused into the institutional DNA.

NYIT’s high-tech environment also means that its global campuses in Nanjing, Beijing, Vancouver, and Abu Dhabi are just a few clicks away through state-of-the-art video conferencing that allows students to create and collaborate with their counterparts on the other NYIT campuses.

Developing a Global Network

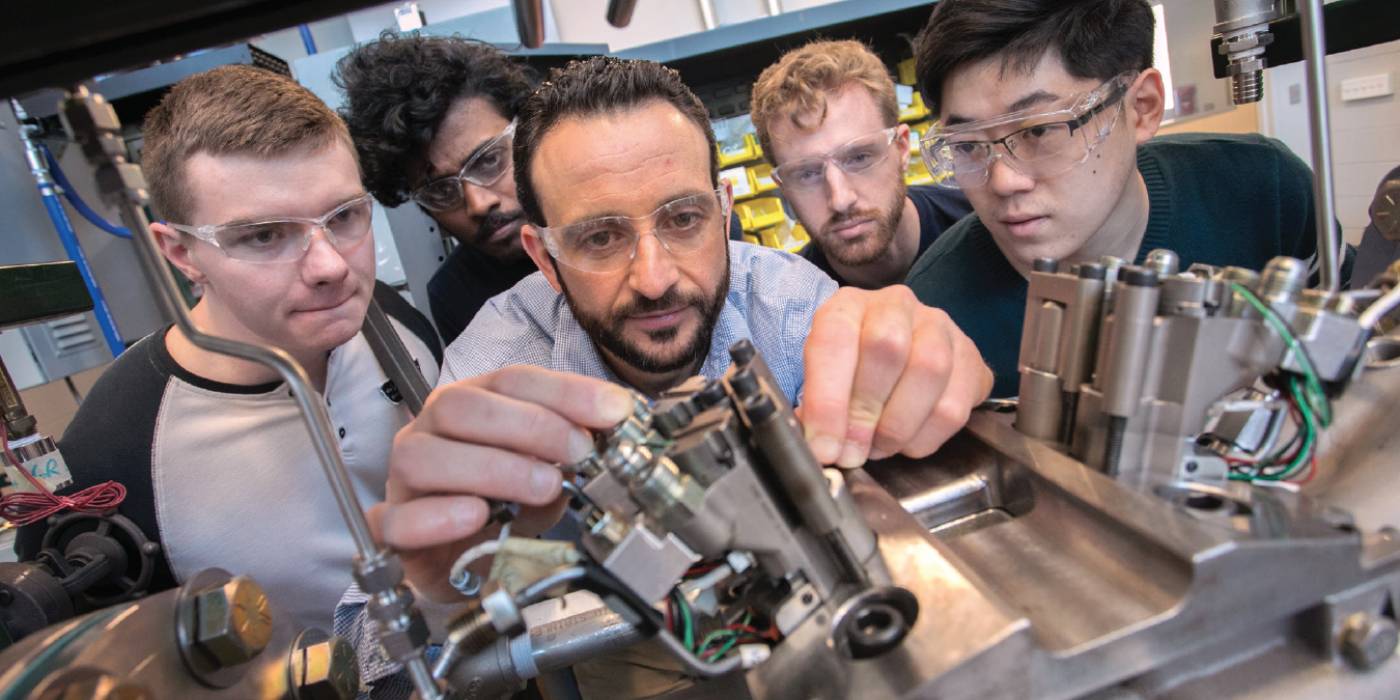

Provost and Vice President for Academic Affairs Rahmat Shoureshi describes NYIT as a high-tech global network. “We have live connections in all of these places, and our students, as well as faculty, can benefit from all of the expertise we have distributed around our network,” he says.

Eschewing the branch campus model, NYIT campuses worldwide follow the same curriculum and are held to the same academic standards. All admissions decisions also go through the Old Westbury campus on Long Island. As Guiliano puts it, “We are one university and offer one curriculum and one degree.”

NYIT also encourages student and faculty mobility between campuses. Students from NYIT-Nanjing, for example, spend their senior year in New York. Shoureshi’s office will also provide travel scholarships for any NYIT student who wants to spend a semester at one of the global campuses. Faculty who propose research that requires collaboration with other campuses receive priority in allocation of research grants.

The first NYIT global program began in China in 1998; the oldest global campus, NYIT-Abu Dhabi, was founded in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) in 2005 as the first licensed and accredited American university in the UAE capital. NYIT-Nanjing opened its doors two years later, followed by NYIT-Vancouver in 2009. Most recently, NYIT opened a second campus in China in collaboration with the Communication University of China (CUC) in Beijing. NYIT has also just opened a new medical school campus on the grounds of Arkansas State University, in a region of the United States where many people lack access to healthcare.

NYIT also offers a number of dual-degree bachelor’s and master’s programs. With Centro Universitário da FEI in São Paulo, Brazilian students in engineering spend two and a half years at FEI, then come to New York for one and a half years, and then return to Brazil for their final year. NYIT also has degree partnerships with more than half a dozen Chinese universities, as well as with institutions in Brazil, France, India, Mexico, Taiwan, and Turkey.

Creating a Positive Experience for International Students

The presence of more than 2,500 international students on the main New York campuses in Manhattan and at Old Westbury on Long Island helps bring the world to NYIT.

Amanjeet Singh, an engineering major from India, feels like NYIT effectively bridges the gap between domestic and international students. He has done his part to help international students integrate into life at NYIT as an international student ambassador, a program managed by the Office of International Education.

“I take care of the freshmen students that come from India or other parts of the world. We have different events and programs so that people can get involved,” he says.

To ensure a positive experience for all international students, the institution convened an international student task force consisting of around 30 faculty and staff in Manhattan and Long Island in 2014–2015. They explored four areas: education, housing and food, jobs and career services, and customer service.

As a result, NYIT created workshops to help faculty and staff understand the challenges international students face, added a range of cultural foods in the dining halls, created on-campus job opportunities, and worked with units across the institution to improve customer service to international students.

The Office of Campus Life also collaborates with the counseling and wellness services offices. For example, it invited in therapists who spoke other languages to help international students understand what counseling entailed, and subsequently saw an uptick in the number of international students seeking counseling services.

Student service, according to Ann Marie Klotz, dean of campus life for Manhattan, is the heart of the NYIT experience. “If I can’t help you, I’m literally going to walk with you to the next office and make sure you have what you need. I think that is the difference maker for a lot of our students,” she explains.

“This is a very special kind of place if you allow yourself to get immersed in the life of students. It doesn’t feel overwhelming. It feels like an overwhelming privilege.”

Preparing Global Professionals

One of the core elements of an NYIT education is to prepare students to enter the job market upon graduation. President Guiliano says that NYIT fosters global competency by providing students with real-world experience and exposure to industry as well as opportunities to work with teams around the world. “Global competency means that work experience, connectivity, and collaboration are really part of what we do in the curriculum.”

Under the rubric of career services, Amy Bravo, assistant dean, oversees experiential education, internships, and service learning. Her office also coordinates job fairs and organizes mock interviews and networking opportunities.

They take special care to ensure that international students are also able to take advantage of opportunities to gain professional skills while still complying with immigration requirements.

Bravo created a number of alternative opportunities for international students to get practical experience. One such initiative is Consultants for the Public Good, which allows all students to work together on projects such as designing a multimedia art gallery for a school cafeteria.

“The idea is to get students to work in teams on community-based projects as opposed to signing up for a volunteer opportunity one time,” Bravo says.

Her office also oversees on-campus employment for both New York campuses. A few years ago, it created a job lottery for student employment, and several positions were earmarked specifically to international students, she says.

Localizing a Global Curriculum

The curriculum remains the same at each campus, but the content of courses can be adapted to the local context. “If students are taking a course in finance in New York, maybe the examples or the case studies are more focused on the types of investments, stocks, and so forth. The same class in Abu Dhabi follows the same curriculum. But the case studies will be on Islamic finance rather than on the stock market,” Shoureshi says.

Harriet Arnone, vice president for planning and assessment, explains it in terms of learning outcomes: “We have to guarantee consistency in learning outcomes across campuses....However, to be relevant to different cultures, particularly as we are so career-oriented, we allow faculty at different locations to add learning outcomes to courses… that reflect the environment...in which graduates will be working.”

NYIT is in the process of developing an occupational therapy program in Vancouver, British Columbia, which must be approved by the Canadian National Organization of Occupational Therapists. Jerry Balentine, DO, vice president for medical affairs and global health, says that as a result, students in the occupational health program in New York will be exposed to more information about the Canadian health care system.

Boosting Student Mobility

Education abroad at NYIT is housed in the Center for Global Academic Exchange, headed by Julie Fratrik. In addition to coordinating services for inbound international students coming to New York from exchanges or other NYIT campuses, her office also offers education abroad advising for outbound domestic students. In 2014–2015, 183 NYIT students participated in education abroad.

Kayla Ho, an American electrical and computer engineering major, spent spring 2015 at NYIT-Nanjing. Her family roots are in China, and she says the experience allowed her to learn more about her heritage as well as about her field of study.

“The chance to go to Nanjing was incredible.... Since it opened its doors, China has been developing technology at an astounding rate; there are new technologies and technology companies being created every day,” she says.

Eriana Burdan, a junior communication arts major, attended one of NYIT’s summer programs with its partner in Paris, École des Nouveaux Métiers de la Communication (EFAP). She took a course in documentary filmmaking that gave her a new perspective on her future media career.

She says it made her think about other career options in her field: “It made me realize that I was pigeonholing myself. There are so many more opportunities in and outside of the United States. It expanded the scope of what I could do with my major.”

Creating Alternative Opportunities to Travel the World

Beyond traditional study abroad, NYIT offers a number of noncredit opportunities for students to travel. Since 2014, President Guiliano has spearheaded Presidential Global Fellowships, which offers awards for NYIT students to engage in research projects, attend global conferences and symposiums, study abroad at another university, or do an internship at international nonprofit organizations.

Guiliano says the goal is to help students have “transformational experiences” at least 200 miles from students’ home campuses. Since the program’s inception, more than 50 students have received awards.

Usman Aslam is a second-year medical student who received a Presidential Global Fellowship in 2015 to travel to Guayaquil, Ecuador, to spend a week working at a mobile cataract surgery clinic, where he was part of a team that performed 128 cataract surgeries. He received $2,500 to cover the cost of his airfare and lodging.

Aslam says that the fellowship was instrumental in his ability to travel. “A grant like this allows us to expand our training, our experiences, and helps mold our understanding of what we want to go into. The fellowship provided me with funding to broaden my perspective on medicine,” he says.

In addition to providing funding for students to create their own “transformative experiences,” NYIT also offers a number of service-learning opportunities abroad. For example, the Office of Career Services organizes an alternative spring break that enabled junior Anthony Holloway to travel to Rivas, Nicaragua, with nine other students to work on a project aimed at improving water quality in the community.

“I had never left the country before,” says Holloway, an interdisciplinary studies major.

Internationalizing the Disciplines

At its New York campuses, NYIT has seven schools and colleges with more than 90 undergraduate, graduate, and professional degree programs. Schools have a variety of faculty-led programs abroad, opportunities to engage with international issues in the classroom, and programs for international students.

The School of Management, for instance, offers four study abroad programs to Costa Rica, India, the Netherlands, and Germany. Students can also do summer internships at destinations around the world.

Every summer, Associate Dean Robert Koenig runs a 27-day business program in New York for 20 students from Hallym University in South Korea. Students take English language and business leadership courses in the morning, and spend afternoons touring business and cultural sites in New York City.

Koenig received the 2015 President’s Award for Student Engagement in Global Education, given to faculty and staff who have made major contributions in the area of global education. His Korea program has been so successful that the School of Management will be launching a similar program next summer with the Tourism College of Zhejiang in Hangzhou, China.

The School of Architecture and Design also has a wide variety of study abroad options for its students. It runs three to four short-term study abroad programs every year, usually in the summer. Approximately 24–40 students participate in these programs per year.

Assistant Professor Farzana Gandhi has worked with a group of students to redesign beach architecture in Puerto Rico and led a program to India that examined the need for affordable mass housing. Many of her courses are focused on social impact design and seek socially and environmentally conscious solutions to global problems such as mass migration, disaster relief, and climate change.

Gandhi says that study abroad has helped her students see their professional practice in a new light: “They have an appreciation for the end user in a much more thorough way.”

From 2012–2014, Gandhi’s students were involved in the Home2O Project, research that led to the development of a roofing system made of recycled plastic bottles and shipping pallets, which has subsequently been patented. Starting with locations like Haiti, they were seeking to develop a kit-of-parts system that could be deployed very quickly at disaster sites in subtropical climates.

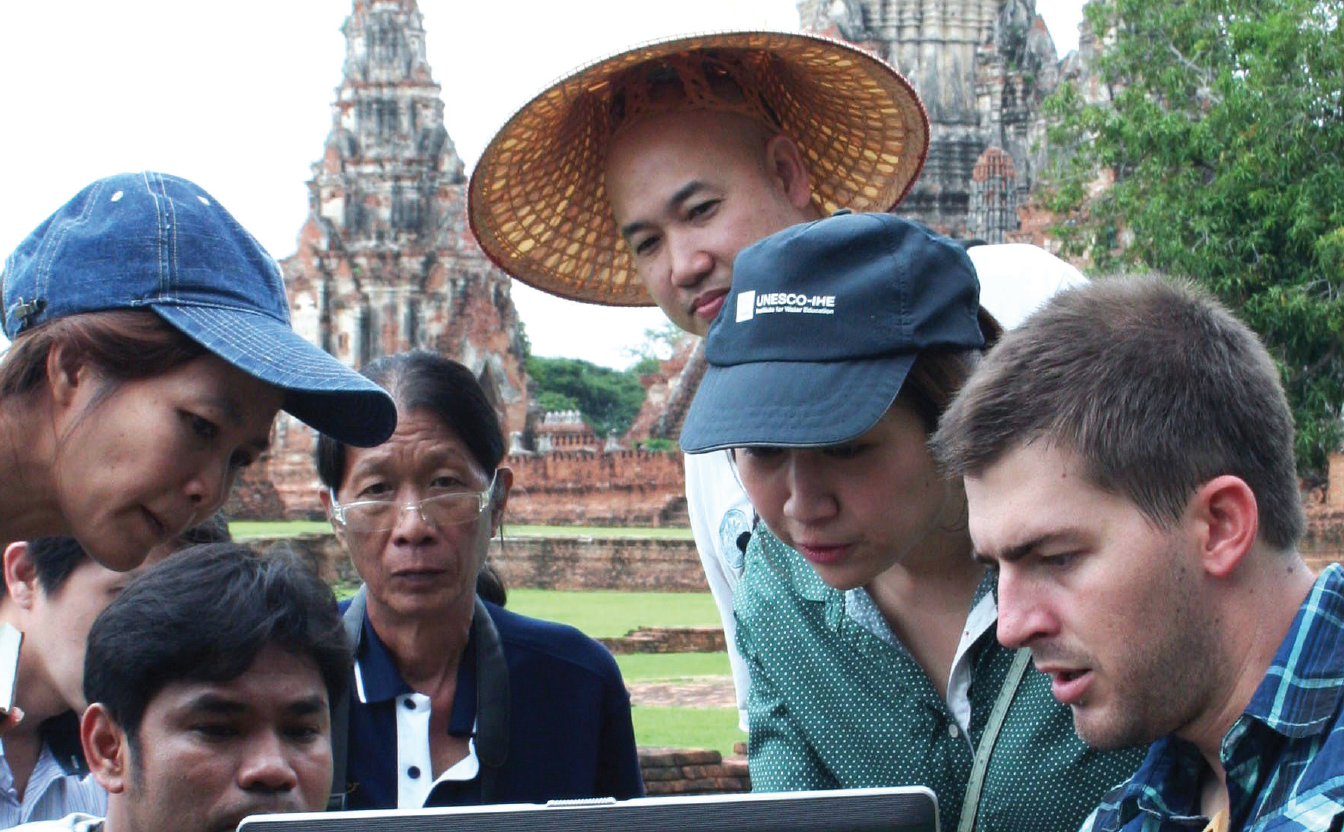

NYIT has also provided support for faculty to pursue international research. School of Architecture and Design Associate Professor Charles Matz, who is also director of NYIT’s Center for Data Visualization, received an institutional grant that allowed him to work with the Ethiopian government and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) to laser scan heritage sites.

He has also worked on a number of joint programs with international partners in countries such as Egypt, the United Kingdom, and Iceland. Matz says that international programs allow students to understand the global standard for the architecture profession.

“Students realize that what they’re doing here is exactly what other people in their situation are dealing with abroad. Their work and its seriousness ramps up because they realize they’re dealing with global issues,” he says.

As vice president for medical affairs and global health, Balentine directs NYIT’s Center for Global Health. “The Center for Global Health really teaches our students about other countries and health care needs there and how to deliver it,” he says.

Through the Center for Global Health, medical students and students in the health professions can pursue a global health certificate. In addition to core courses, students do global health fieldwork, a 2–4 week program where students deliver health care services in countries such as Haiti and Ghana. They also complete an independent research project on global health under faculty supervision.

Balentine says the goal of the certificate is much broader than just getting students to go abroad. “From a teacher’s point of view, the real value is that even if these students never again leave the U.S. to practice medicine, the experience, the difference in health care that they see, the difference in living, the difference in cultures that they see, makes them better physicians back home,” he explains.

NYIT’s College of Osteopathic Medicine also offers a unique Émigré Physicians Program, which each year enrolls approximately 30 students who were trained physicians in their home countries. It’s one of the few programs of its kind in the United States.

Paving the Way to the Future

In 2015 the institution launched a new long-term strategic plan, known as NYIT 2030 version 2.0. According to Arnone, “When the plan was first published in 2006 the emphasis was on NYIT’s footprint and its additional locations overseas. In the revised plan, the language of the relevant goal now focuses on the global impact of an NYIT education; correspondingly, the priority initiative in support of this goal focuses on increasing opportunities for deep engagement across cultures.”