Gearing Up for Growth

After becoming the University of Maryland-Baltimore County (UMBC)’s first senior international officer (SIO) 2 years ago, David Di Maria began efforts to put the university’s international programs on stronger financial footing—not with a spreadsheet or a calculator, butwith a highlighter.

“I sat down and read the university’s strategic plan and highlighted everything where internationalization could push the needle,” says Di Maria, UMBC’s associate vice provost for international education. “I wanted the deans, the faculty, and the student affairs department to see themselves in the plan so they could engage in the international dimensions.”

For international offices at many institutions, this holistic approach to strategic planning isn’t just about collegiality; it’s a matter of survival. The ongoing decline in international student enrollment is doing more than straining offices and programs. With their parent institutions confronting declining domestic enrollment, international offices face financial challenges that, if unaddressed, could put the entire internationalization movement at risk.

“You have to be financially savvy nowadays because the age of not worrying about where the money is coming from is gone,” says Paulo Zagalo-Melo, associate provost for global education at Western Michigan University. For SIOs, keeping their offices financially sustainable means rethinking how international programs are funded and seeking new, often entrepreneurial, ways to diversify revenue streams. For many, this work represents a complete upending of budgets and priorities, according to Di Maria.

“A lot of the investments in internationalization at colleges and universities were driven by enrollment bubbles,” he says. “Because there hasn’t been a strategy for providing resources to internationalization, it’s been cobbled together in ad hoc fashion.”

The IEP Wave—and Crash

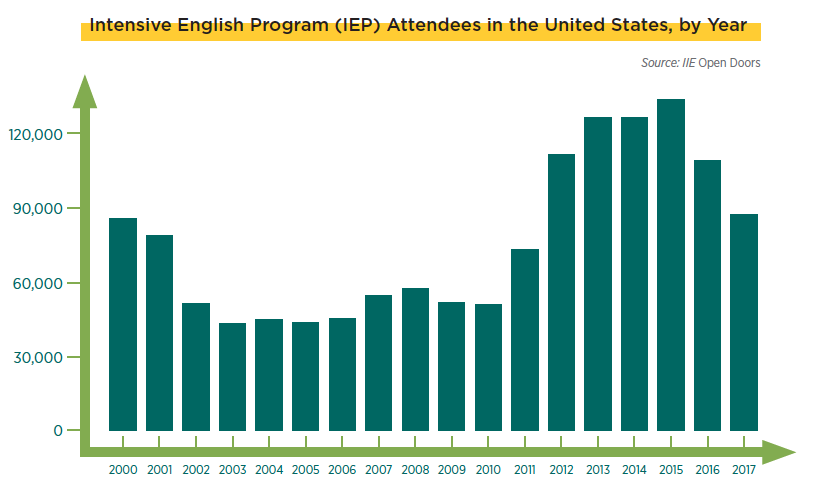

Part of that enrollment bubble has centered on intensive English programs (IEPs), which surged in popularity over the past decade. Tuition from IEPs was often used to fund new international staff and programming. Coupled with broader enrollment gains—the number of international students enrolled in U.S. institutions hit a high-water mark during the 2015–16 academic year—IEPs helped ensure that international offices had the financial stability to expand programs and services during the first half of the decade.

Some offices ran surpluses for nearly a decade, according to Zagalo-Melo. Many, adds Di Maria, “did multimilliondollar renovations and doubled or more than doubled staff. Then all of that came crashing down.”

As overall international enrollment began falling in 2016–17, institutions with IEPs saw more drastic declines. In 2015, more than 133,000 international students were enrolled in IEPs at U.S. institutions, according to the Institute of International Education (IIE)’s Open Doors data. Numbers have since fallen by more than 35 percent to 86,000 in 2017, the most recent year for which data are available. The impact has been even more pronounced at institutions whose IEPs focused on specific countries.

When times were good, many institutions moved away from allocating money from the general fund for international staff and offices, relying instead on tuition revenue and sponsored student fees. Then, as the numbers of inbound international students began to decline, additional compliance and reporting regulations increased, exacerbating the financial crunch and forcing SIOs to confront what Zagalo-Melo calls a “flawed” financial model.

Too many institutions “let that growth in a very unpredictable type of enrollment govern the extension of services,” he says. “It was a major flaw in strategic management.”

While managing budgets may not be the reason why most international educators entered the profession, the financial realities confronted by today’s offices make it a vital part of the role. NAFSA considers financial stewardship an essential competency for all international educators, and SIOs must take a close look at how their programs are funded and how they now operate given existing fees and budget structures. Only then, SIOs say, is it possible to map out a more sustainable course.

“There’s no one strategy that’s going to work for everyone,” says Jesse Lutabingwa, associate vice chancellor of international education and development at Appalachian State University. “Understanding the options that are available becomes very important.”

A Diverse Portfolio

Revenue diversification isn’t new in higher education—it’s essentially how all institutions try to stay in the black.

“The overall outlook of the university depends upon maintaining a strong diversified portfolio of offerings where some departments cross-subsidize others and some graduate schools are more revenue-positive than others,” says Erich Dietrich, assistant vice president for global programs and associate dean of global affairs at New York University (NYU). Many international offices already employ a similar approach, having intensified efforts to recruit students from a growing number of countries in recent years.

Dietrich offers a succinct suggestion on how to identify opportunities for partnerships. “Success breeds success,” he says. “Those most likely to gain additional research are the ones successful with research.” At NYU, international research partnerships jointly coordinated by the research and international offices represent “a great opportunity for continued collaboration,” Dietrich says.

At UMBC, a partnership cultivated with a vice provost from another department funded a new position in the international office that supports a shared program. The goal, Di Maria says, is “not being seen as a stand-alone entity and competitor for resources. You’re a partner in achieving their objectives.”

Partnerships with third-party providers—pathway providers, third-party IEP programs, and other outside organizations—can cultivate dedicated funding sources. At UMBC, for example, one third-party provider returns 10 percent of its revenue to the international office. Other providers may compensate international offices with in-kind recruitment travel, reduced costs for overseas programs, or local staff to support international office activities.

Fundraising Opportunities

A growing number of international offices are focusing on engaging international alumni in fundraising efforts. The key, Di Maria says, is not seeking big-ticket donations from a few wealthy alumni, “but developing that culture of giving back early.” Even small donations can have an outsized impact on student services, such as helping offset travel expenses or providing study abroad scholarships.

However, fundraising is not always an area of expertise among international educators. At Appalachian State, Lutabingwa developed his skills as a fundraiser by attending conferences and partnering with a member of the institution’s advancement office, who ultimately became the international office’s liaison. “We travel together to visit donors,” he says. “She knows how to do the asking, and I know how to tell the stories.”

‘Leaky Faucets’ and Low-Hanging Fruit

Identifying seemingly smaller opportunities for cost savings and new revenue can boost the bottom line in more ways than one. Third-party providers serving large numbers of students may indicate untapped demand, as well as opportunities to bring study abroad programs in-house at lower costs. Responsibilities handled by retiring support staff may be reallocated as shared services with other departments or a central administrative office. Targeted fees can also help offset the costs of services such as immigration compliance.

Smaller collaborations on and off campus can result in quick wins. At Appalachian State, partnerships with the bookstore and student affairs office provide supplies and additional services to international students during their orientation week, says Lutabingwa. To both raise revenue and promote intercultural engagement, some international offices open up campus events, such as international festivals, to the larger community. Tickets and sponsorships to such events tend to be consistent sources of revenue, says Di Maria.

Institutions can offer their own “boutique programs”—study abroad opportunities that leverage unique faculty relationships with international partners—to students at other institutions, Di Maria says. Noncredit education and high school programs also provide new revenue sources, according to Dietrich. And don’t count out IEPs, says Lutabingwa—while many programs have scaled back in light of declining enrollment, “they are still generating revenue,” he says.

In some cases, it may be possible to negotiate with college leadership a “finder’s fee”—often a percentage of the cost savings—to come back to the office as unrestricted funds, Di Maria says. More importantly, these efforts position SIOs as problem solvers, and “that engages you in the conversation,” he says.

A Mindset Shift

Exploring these strategies often involves a new but vital skill set for many SIOs. “Internationalization must have a business plan,” Di Maria says. “You have to have an entrepreneurial mindset and engage in ways to build your office.” First and foremost, doing so requires patience and perseverance.

“I would encourage people to take as long a view as possible because it can really take time to build these things up,” says NYU’s Dietrich, calling revenue diversification “a three- to five-year strategy at least.” But, he cautions, “the number one way of ensuring revenue for the future” remains prioritizing quality across all programs and partnerships.

Understanding how the institution handles its finances is critical. Institutions use a wide range of budget models, from responsibility- and performance-based models to baseline or zero-based budgeting. This knowledge, says Di Maria, can help SIOs determine how to ensure that their institution’s general fund can cover core operations while identifying the revenue flows that support other programming. “It’s a major mindset shift,” says Zagalo-Melo.

Even as SIOs develop their range of capacities, it is important to bring the entire office along, says Dietrich, who encourages professional development opportunities that go beyond international education and into areas such as research. Lutabingwa agrees, noting that when he arrived at Appalachian State, none of his office’s three directors had budgetary responsibilities.

“That’s the group from which we recruit new senior international officers,” he says. “We need to empower them.” Bring staff “into the conversation,” advises Zagalo-Melo. “Show them where the flaws of the budget model are.”

Another vital step is to win support from senior leadership and have them “understand your narrative,” Zagalo-Melo says. For SIOs, that can mean stepping back and looking at the bigger picture. “Understand what the institution has stated as its goals,” says Di Maria. “What are its pain points? If you can be seen as a way to release some of that pressure for administrators, you’re not seen as another person competing for a limited pie, but a partner who is contributing to a goal.”

Above all, efforts to diversify revenue sources should go beyond budgets and the bottom line—they should dovetail with broader institutional aspirations around internationalization.

“The role of the senior international officer is being a facilitator,” Di Maria says. “We need to try to encourage people to move forward together.

Financial Stewardship and International Education

NAFSA considers financial stewardship a crosscutting professional competency for all international educators. Along with direct service and management responsibilities, international educators should be able to:

- Analyze financial data.

- Collaborate with other offices on campus around fundraising.

- Coordinate international education-related grant development across campus departments.

- Develop finance, budget, and funding policies in line with institutional policies.

- Explore and initiate fundraising opportunities, including writing and submitting grants.

- Identify and pursue new revenue opportunities.

- Make resource allocation decisions based on analysis.

- Plan, manage, and oversee budgets.

- Propose and negotiate annual budget using institution’s financial model.

Source: NAFSA International Education Professional Competencies

NAFSA Resources

Additional Resources

About International Educator

International Educator is NAFSA’s flagship publication and has been published continually since 1990. As a record of the association and the field of international education, IE includes articles on a variety of topics, trends, and issues facing NAFSA members and their work.

From in-depth features to interviews with thought leaders and columns tailored to NAFSA’s knowledge communities, IE provides must-read context and analysis to those working around the globe to advance international education and exchange.

About NAFSA

NAFSA: Association of International Educators is the world's largest nonprofit association dedicated to international education and exchange. NAFSA serves the needs of more than 10,000 members and international educators worldwide at more than 3,500 institutions, in over 150 countries.

NAFSA membership provides you with unmatched access to best-in-class programs, critical updates, and resources to professionalize your practice. Members gain unrivaled opportunities to partner with experienced international education leaders.