Danger and Opportunity: Responding to Change Dynamics in the Field

There are many change dynamics currently impacting higher education and post-COVID internationalization. Urgent aspects of reform include cost control, accountability to documentable and socially relevant outcomes, and shifts toward learner-oriented pedagogy and content. Some critics of higher education suggest that it is facing a crisis in terms of high cost and doubtful outcomes.

A similar set of critiques applied to international education and internationalization provided the basis for some to suggest the end of the “golden age” of internationalization. In reality, globalization remains a powerful force; internationalization and international education haven’t gone away and will not. Rather, they will necessarily undergo elaboration and revision in order to remain relevant in a twenty-first century context.

Two Chinese characters form the concept of crisis—one for danger and the other for opportunity. A window for change has opened because the COVID crisis demonstrated the possibility for change in both higher education and international education. It would be unfortunate if opportunity to improve was lost to preserving the old normal. Disruption births opportunity for change if aimed at improving outcomes.

Action to Move Forward

There are several core changes needed for higher education internationalization to be responsive to challenges. Two foundation blocks for sustainable responsiveness involve the intelligent use of technology and the integration of internationalization into all institutional core missions. There are also implications for outbound and inbound mobility, curricular integration, public and community service, documenting measurable outcomes, and building cross-border inter-institutional partnerships.

Leverage Technology in Change and Reform

Online learning and virtual meetings were principal “coping” mechanisms used during COVID’s early years. Will the expanded use of technology survive as we emerge from the pandemic? The most likely answer is that its use will increase to widen access and reduce costs; it will become a more frequent supplement to, but not a mass substitute for, face-to-face conferencing and learning.

A recent report by UNESCO-IESALC has an intriguing and possibly prescient title: “Moving Minds: Opportunities and Challenges for Virtual Student Mobility in a Post-Pandemic World.” It notes that the conscious blending of digital and face-to-face learning in curricula is most needed and will apply to both inbound and outbound mobility, as well as to internationalizing curricula at home. The report provides a useful typology of types of virtual learning models.

Integrate International Education and Internationalization Throughout Institutional Missions and Culture

It is an indispensable strategy to integrate internationalization into higher education’s three core missions: teaching/learning; research/scholarship; and community engagement/problem solving. Connecting international education to faculty and academic unit core missions builds salient institutional support, and internationalization of faculty and faculty mobility are vital. Informing and incentivizing a wide array and number of academic personnel to participate in internationalization efforts involves connecting their jobs to an institutional culture that supports international activity across all missions.

Without integration into core missions, internationalization and mobility are easily viewed as appendages—nice to let an international office do, but not part of higher education’s core work. As such, they are easily chopped off or disregarded under resource scarcity (or from other challenges such as COVID).

Even outside of a resource-scarce environment, internationalization is inherently marginalized without a broad-based institutional culture to support it, and it will likely fail to reach its full potential on campus. A starting point to creating such a culture is to initiate an institution-wide dialog. The conversation should provide compelling answers to: What is internationalization; why do it; how does it enhance institutional missions and peoples’ jobs; what outcomes should be expected or desired; and who has roles to play?

The purpose of dialog is to educate, build support and buy-in, gather attention to internationalization, and establish an institutional expectation of broad-based involvement in international education and internationalization.

Reposition Outbound and Inbound Mobility

Integration has been the weak link in formulations of higher education internationalization over the last several decades. In part this is because student mobility has been the most powerful operational definition of internationalization, and its public face for many. Outbound U.S. student mobility and internationalization are often seen as synonyms at many institutions, when in reality the former is only a key part of the latter. Standing alone, both are marginalized.

The importance of student mobility cannot be over-emphasized. However, mobility needs strong connections to other facets of internationalization (e.g., internationalizing on-campus curricula, building international partnerships across missions, strengthening institutional research capacity through global connections, and internationalizing community and public service). With only 2–4 percent of students being mobile in the United States—a bit higher in some world regions, much lower in others—operationalizing internationalization mainly through the outbound mobility of students who can afford it does little to advance access, equity, and diversity in international education.

In many large institutions, international education is seen as the responsibility of the international office, the study abroad office, and the international student office. These are essential support entities, but not academic units per se. Outbound mobility generally doesn’t count much in academic promotion and tenure, institutional resource allocations, and unit academic reputations. Most damaging to integration is the oft heard, “our education abroad office handles study abroad, the office for international students supports them”—the implication being “so the rest of campus need not be bothered.”

Outbound Mobility

Education abroad and internationalization need voices at the tables of departmental, college, and university curriculum planning processes. Here are some ideas for gaining entre:

- Link the design of study abroad programs to the content and learning goals of curricula, rather than accommodating education abroad or international students as afterthoughts or for revenue.

- Make faculty and academic departments integral to the study abroad design process, and, in some cases, through faculty on-site involvement in programs. Faculty engagement is essential for integration; numerous faculty have had their careers internationalized through involvement in student mobility.

- Design campus-based curricula to provide the intellectual foundation for pre-departure preparation and for post-program debriefing and synthesis. Make study abroad a more active learning component of internationalizing learning generally.

- When possible, develop cross-border inter-institutional courses combining students, faculty, and ideas from multiple institutions by using cost-effective technology (e.g, Zoom, curated flip facilitated programming, and COIL).

- Diversify study abroad options linked to the curriculum (short and longer programs, incorporating virtual options and active learning options, and virtual internships). Diversifying options expands access.

Inbound Mobility

If international students are seen mainly as a revenue-producing commodity without attention to services to meet their needs, eventually they will stop coming, especially given the expansion of options for them globally. Failure to nurture and connect international students to the campus living and learning environment is anathema to the purposes of international education, and a lost opportunity for internationalizing on-campus curricula and its environment. Yet, the spread of mercantile international student recruitment is an unfortunate reality globally.

Harness for international students all the usual services available for domestic students across student and scholar services, admission and enrollment, and academic units. Producing value for money is essential to preserving markets. Most importantly, service to and integration of international students into living and learning environments inherently contributes to institutional internationalization.

Engage Communities

There is a renewed emphasis on the societal roles and public benefits of higher education. Can internationalization be seen to benefit society with socially relevant outcomes? Earlier objectives of higher education were knowledge, skill, and perspective development in a particular field. It is now equally a wider set of purposes and constituencies to be served (e.g., societal needs, community problem solving, and employers). International education is also responsible for helping create a citizenry and workforce capable of living and working in a global environment.

Community engagement builds public and political support for internationalization by producing job-ready graduates for a local economy tied to a global market and economy; helping communities cope with global forces; and connecting local products to global markets. Communities need to be consulted on needs and priorities with respect to global challenges and opportunities; higher education needs to be seen contributing to these negotiated priorities.

Document Measurable Outcomes

Higher education and internationalization do an inadequate, poor job of documenting measurable outcomes relevant to a twenty-first century society. The dominant measures of “success” are suboptimal such as the number of students studying abroad in diverse locations, the number of memorandums of understanding (MOUs) with institutions abroad, or the dollar value of grants and contracts. Inadequate attention is paid to answering the “so what?” question—namely, we spend a lot of money and there is a lot of activity, but what of value do we get from it?

Assessment, and ultimately public support, for internationalization depends on evidence that desirable outcomes are advanced: a) preparing all learners for life and work in a global environment; b) connecting to global sources of talent and ideas; c) and helping local communities negotiate the global through programs of civic and community engagement.

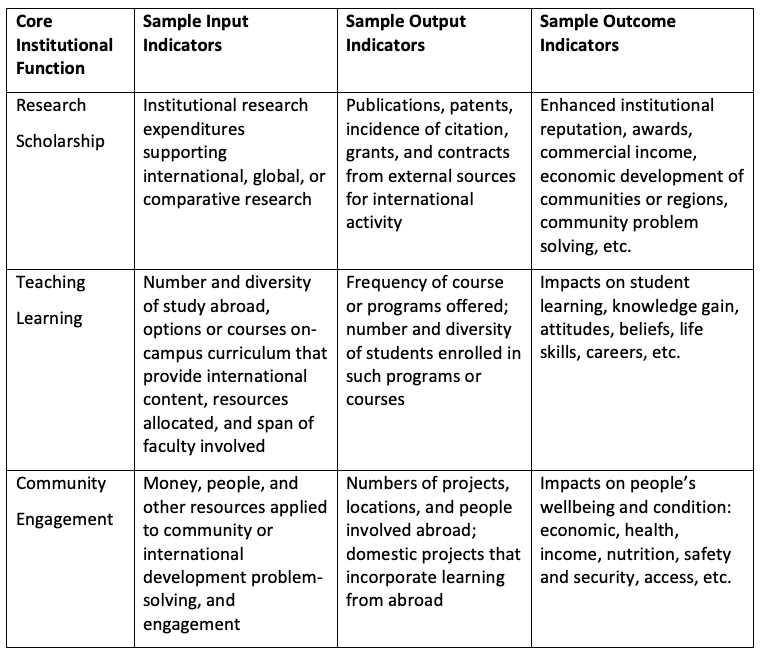

Failure to address these issues contributes substantially to doubts about the value of higher education internationalization, because the suboptimal measures call attention to cost and activity but not results. The table below highlights the differences among outcome and other kinds of measures.

Dimensions of Assessing Internationalization

Internationalization competes with a myriad of institutional agendas for scarce resources. Pressures to reduce higher education costs place a premium on activities and expenditures that produce valued results. “We’ve spent a lot of money, or did a lot of work,” are not inherently valued in the competition for scarce resources. Rather, it is what we get in valued results that counts.

Bolster Cross-Border Inter-Institutional Partnerships

Much of the previously discussed methods, while not dependent on partnerships and networks of institutions per se, are clearly made more productive if institutions form multi-missioned partnerships with institutions abroad to widen access to ideas and talent. Partnerships have cost- sharing, cost-reduction, and knowledge access implications if they are more than the paper MOUs. Partnerships are not automatically productive but are heavily dependent on trust and openness, giving relationships time to develop, and agreement on principles before programs.

The value of partnerships increases when multiple missions can be served: teaching and learning; research; and community problem solving. For example, including student participation in field research and service learning, or taking a study abroad site into research priorities.

Effective partnerships at base must include a mutuality of benefit—each partner benefits through broad agreement on goals and follow through in contributing. Exploitation doesn’t work, particularly in the longer run. Partnerships for the sake of partnership (or “club” membership) is largely a waste of time and money.

What’s Next?

The future of higher education internationalization does not reside in a return to a pre-COVID normal. It is found in addressing contemporary pressures for change in higher education which have parallel implications for internationalization. Among the more salient of change pressures are controlling costs. Equally salient is to enhance and publicly document learning and socially-relevant outcomes from higher education and its internationalization. When it comes to international programs, the blended and intelligent use of technology has a special role to play in meeting sustainability goals and cost control generally.

However, for a more robust internationalization future, the most fundamental need is to strengthen internal and external support for it. The key strategies for doing so involve the long-term building and nurturing of an institutional cultural for internationalization and, relatedly, integration of it into all institutional core missions. Success in this regard is dependent on active faculty and academic staff engagement.

The future of higher education internationalization is what we choose to make it by seizing opportunities for change and improvement. The strategies and tactics laid out are not easy to accomplish but essential for a more robust future. •

About International Educator

International Educator is NAFSA’s flagship publication and has been published continually since 1990. As a record of the association and the field of international education, IE includes articles on a variety of topics, trends, and issues facing NAFSA members and their work.

From in-depth features to interviews with thought leaders and columns tailored to NAFSA’s knowledge communities, IE provides must-read context and analysis to those working around the globe to advance international education and exchange.

About NAFSA

NAFSA: Association of International Educators is the world's largest nonprofit association dedicated to international education and exchange. NAFSA serves the needs of more than 10,000 members and international educators worldwide at more than 3,500 institutions, in over 150 countries.

NAFSA membership provides you with unmatched access to best-in-class programs, critical updates, and resources to professionalize your practice. Members gain unrivaled opportunities to partner with experienced international education leaders.